ABSTRACT

Systemic capillary leak syndrome is a rare, underdiagnosed and life-threatening disease characterized by periodic episodes of hypovolaemic shock due to leakage of plasma from the intravascular to the extravascular space. It is associated with haemoconcentration, hypoalbuminaemia and generalized oedema.

We report the case of a patient with a history of emergent extensive small and large bowel resection and several episodes of hypovolaemic shock with acute renal injury, who presented with abdominal pain, headache and generalized oedema. Severe systemic capillary leak syndrome was diagnosed after a complex diagnostic approach. This case report describes the acute and prophylactic treatment administered to the patient and the 4-year follow-up. We highlight the importance of timely recognition and prompt treatment, as well as the need for new investigations to prevent the serious and unusual complications seen in this case.

LEARNING POINTS

- Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (ISCLS) should be suspected in the presence of the triad of hypotension, haemoconcentration and hypoalbuminaemia; the diagnostic work-up is challenging and requires exclusion of several causes of hypotension and shock of uncertain aetiology.

- Acute mesenteric ischaemia leading to extensive and emergent bowel resection is an irreversible but atypical complication of ISCLS; other complications include myocardial oedema and deep vein thrombosis.

- ISCLS is characterized by three phases; supportive as well as prophylactic treatment adapted to each phase is crucial for prognosis and to avoid end-organ damage.

KEYWORDS

Idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (ISCLS), hypovolaemic shock, monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia, acute kidney injury

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old man with a medical history of smoking and significant bowel resection 2 years previously presented to the emergency department complaining of intense headache and abdominal pain that had started 2 days earlier. He also reported dyspnoea, generalized oedema, asthenia and a decrease in urinary output in the last week. He did not describe fever or other neurological, respiratory, digestive or genitourinary symptoms. He worked as a hairdresser and denied allergies, exposure to new substances, drugs, ticks, animals or recent travels.

He had been submitted to extensive small and large bowel partial resection 2 years previously, which had resulted in post-surgical short bowel syndrome and a colostomy. At that time, he had presented with non-specific abdominal pain, hypotension, elevated plasma lactate levels, an elevated haematocrit consistent with haemoconcentration, and metabolic acidosis. Plasma creatine phosphokinase levels were normal. After abdominal CT arteriography had excluded several causes of shock including arterial occlusion and venous thrombosis, intensive haemodynamic support and monitoring was provided. Emergent abdominal exploration and bowel resection was then carried out. The diagnostic approach included exclusion of several causes of end-organ damage including cardiovascular disease, sepsis and drugs. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia was identified as the most likely cause.

The patient required two more surgeries for partial bowel resection. Post-surgery care was complicated by catheter-related superior vena cava thrombosis associated with the implantation of a vascular access system for parenteral nutrition, which resulted in the patient needing 3 months of hypocoagulation.

The patient also reported three previous hospitalizations for oliguric acute renal injury before his bowel surgery. In the first episode, 3 years previously, he presented with hypovolaemic shock and metabolic acidaemia requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission for ionotropic support, renal replacement treatment and broad spectrum empiric antibiotics as the primary cause remained unknown. The episodes were all preceded by a 2-day prodrome of intense headache and diffuse abdominal discomfort associated with physical exercise and heat exposure.

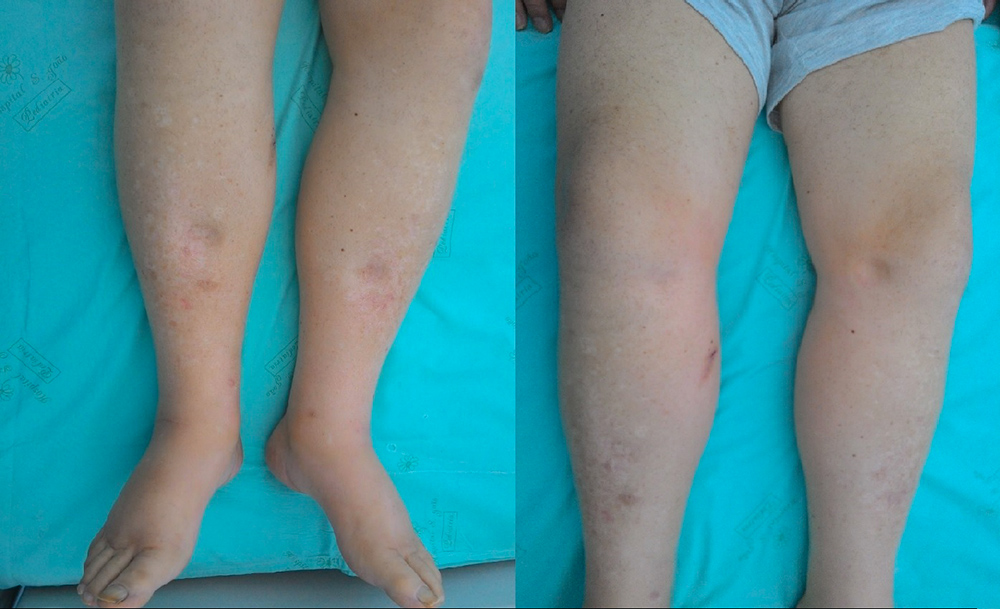

Physical examination in the present hospital admission showed the patient was haemodynamically unstable with hypotension (85/45 mmHg) and a heart rate of 120 bpm, but without respiratory failure or fever. He presented with generalized oedema, but no skin flushing, urticaria, focal angioedema, stridor or lymphadenopathy was detected (Fig. 1). His abdominal, neurological, cardiac and pulmonary evaluations were normal.

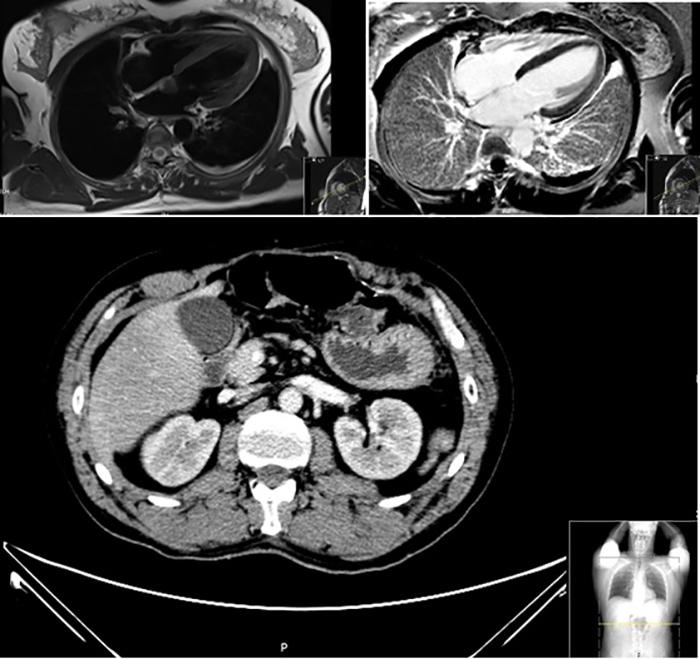

Arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe metabolic acidaemia (pH 7.27, HCO3 10.6). Laboratory findings showed haemoconcentration with Hgb 22.4 g/dl (normal 13.5–18.0 g/dl), haematocrit 61% (normal >49–50% in men), 20.08 K/µl leucocytes (normal 4–10 K/µl), uraemia (90 mg/dl; normal 6–23 mg/dl) with elevated creatinine (2.20 mg/dl; normal 0.50–1.20 mg/dl) and hypoalbuminaemia (2.0 g/dl; normal 3.5–5.2 g/dl). Creatine phosphokinase (CPK), coagulation and liver function were normal. Elevated BNP (222.5 pg/ml) with a normal troponin level was documented. An electrocardiogram did not show any relevant disturbances. A thoracic x-ray, urinary study with 24-hour urine collection, a contrast-enhanced thoracoabdominal CT scan, and abdominal and renal ultrasound were all normal (Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Physical examination revealed significant and generalized oedema

Top panels: cardiovascular MRI did not show any relevant changes. Bottom panel: contrast-enhanced CT image of the abdomen without signs of acute ischaemic or non-viable gastrointestinal segments

The patient started intensive fluid replacement therapy and was admitted to the Internal Medicine Department after haemodynamic stabilization with renal function recovery.

Inflammatory studies including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) did not show any relevant changes. A complete infectious study involving serologies, blood and urinary cultures was performed and was negative.

In light of the several episodes of severe hypovolaemic shock with acute renal injury, generalized oedema and laboratory findings of haemoconcentration and hypoalbuminaemia, the diagnosis of idiopathic systemic capillary leak syndrome (ISCLS) was suspected. The prodromes of intense headache and abdominal pain, as well as the association with previous heat exposure, supported this diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis also included sepsis, anaphylaxis and some drug reactions. Several causes of distributive, cardiogenic, hypovolaemic and obstructive shock were considered and excluded.

Studies of thyroid, gonadal and adrenal steroid function, and immune and metabolic function tests were unremarkable. Complement studies including C3, C4 and CH50 as well as C1 esterase inhibitor levels and function to exclude types I and II hereditary angioedema, were requested and were normal.

A complete cardiac study was performed to identify causes of hypotension or shock of uncertain aetiology, and to investigate dangerous cardiovascular complications associated with ISCLS, especially in the recruitment phase. Transthoracic echocardiography and cardiovascular MRI did not show any relevant changes (Fig. 2).

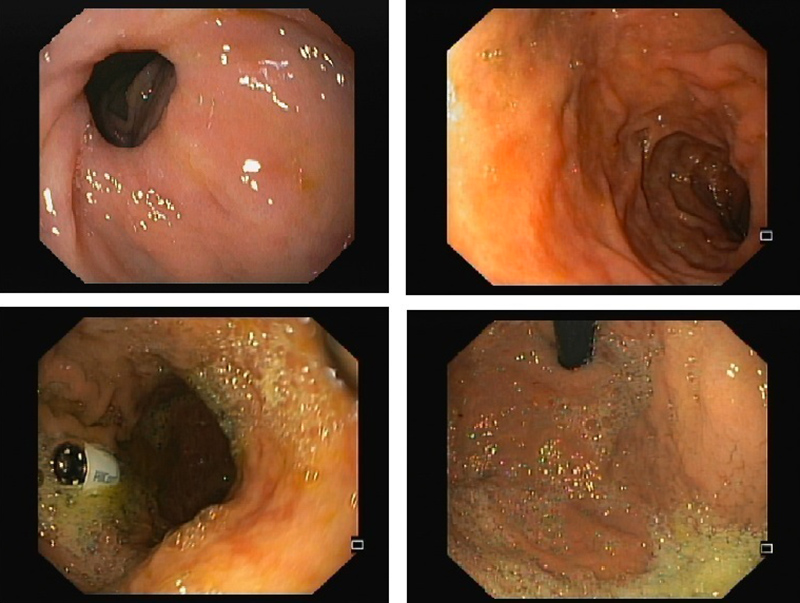

A whole endoscopic study was requested because of the severe gastrointestinal presentation and the association between neuroendocrine tumours and acute severe hypovolaemic episodes, but did not show any relevant changes (Fig. 3).

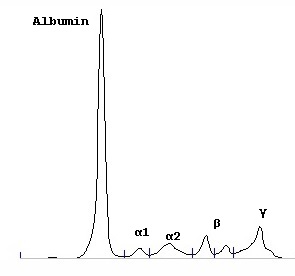

Since ISCLS is related to monoclonal gammopathies, a complete study with serum protein electrophoresis, urine protein electrophoresis, immunofixation and serum free light chain assay was performed and revealed a monoclonal gamma/lambda gammopathy (IgG1) of unknown significance with lambda light chains (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Upper and small bowel capsule endoscopy did not show any lesions or other relevant changes

Figure 4. Serum protein electrophoresis revealing monoclonal gamma/lambda gammopathy (IgG1) of unknown significance with lambda light chains, confirmed by an immunofixation study

Immunocytochemical evaluation of a bone marrow biopsy specimen did not show any disturbances.

After the diagnosis was made, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (1 g/kg) was administered, resulting in considerable improvement in the patient's clinical status. He maintained nutritional supplementation due to the short bowel syndrome and was discharged 1 month later.

During follow-up, the patient reported several episodes of oedema of the extremities and fatigue due to partial leaks and therefore started prophylactic treatment with terbutaline and theophylline, requiring periodic plasma level evaluations for 2 years.

The patient avoided physical exercise and heat exposure, but still needed two more hospital admissions for acute exacerbation associated with subtherapeutic theophylline levels. He then started prophylactic administration of 1 g/kg/month IVIG, which he maintained for 1 year with good results.

DISCUSSION

This case report is remarkable for both its rarity and the severe systemic manifestations, difficult diagnostic approach and unusual irreversible complications. It concerns a patient with a history of major and emergent bowel resection and several episodes of hypovolaemic shock with acute renal injury, who presented with abdominal pain, acute headache and generalized oedema. A complex diagnosis of ISCLS (also known as Clarkson disease) was made after exclusion of other rare disorders such as hereditary angioedema and neuroendocrine tumours.

Although <500 cases of ISCLS have been reported in the literature since 1960, the condition is probably under-diagnosed due to lack of awareness and a high mortality rate without treatment[1]. It typically begins in midlife and diagnosis relies on the triad of severe hypotension, hypoalbuminaemia and haemoconcentration[1,2].

Despite the association of ISCLS with monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, evolution to myeloma is not inevitable[1]. However, this can influence treatment strategies, like the administration of IVIG, as in the follow-up of this patient[3].

Prodromes with intense headache and abdominal pain with previous heat exposure have been reported but are less frequent than those which include upper respiratory infections. Prodrome symptoms and their triggers are under study but have not yet been defined[1,2].

This case is also unusual because of the severe episodes of multiple organ failure and end-organ complications, such as the need for nutritional supplementation after bowel resection and deep venous thrombosis. The most commonly reported gastrointestinal consequences are compartment syndrome during both the extravasation and recovery phases and ischaemic hepatitis due to prolonged hypoperfusion.

This report underlines the importance of cardiovascular evaluation because myocardial dysfunction is frequent in patients with SCLS and because overly aggressive fluid resuscitation can lead to pulmonary oedema and compartment syndrome in the recovery (fluid recruitment) phase[4].

We emphasise that the cornerstone of acute treatment remains supportive care with intense haemodynamic stabilization and monitoring, although other treatments are under investigation, including the administration of high doses of IVIG, intravenous aminophylline and terbutaline, as well as anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antibody[3,4]. The administration of IVIG was effective in our patient.

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia remains a rare emergent condition, especially in young patients without known risk factors, and requires early recognition and timely treatment in order to prevent serious consequences[5]. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia has a mortality rate of 70–90%, which has changed little over time despite new treatments.

This case report describing a patient requiring a prompt laparotomy which disclosed massive bowel necrosis, emphasises the importance of identifying ISCLS as a predisposing disease underlying mesenteric ischaemia. In addition to the high degree of clinical suspicion and emergent haemodynamic support required, we also underline the severe and permanent gastrointestinal consequences in our patient which included malabsorption syndrome, a colostomy and associated infective, thrombotic and haemodynamic comorbidities (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. A colostomy bag after emergent and significant bowel resection resulting in short bowel syndrome

Detailed observational studies combined with personalized investigation are crucial and may provide a better understanding of the immunology underlying the exaggerated microvascular response leading to capillary leak syndrome, as well as improve the diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemia and ISCLS.