ABSTRACT

A 43-year-old man complaining of abdominal angina for several months showed a large suprarenal aneurysm of the abdominal aorta with extensive circumferential wall thrombosis, complete occlusion of the right renal artery and a critically stenosed left renal artery on CT angiography. He suffered from severe hypertension and renal failure. A percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) was planned. After the PTA procedure, which was complicated by the development of left renal artery occlusion, successful rescue revascularization surgery was performed. Since we were hesitant to start anticoagulant treatment because of a high bleeding risk, magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging was performed to assess the age of the extensive arterial thrombosis. The aortic thrombus showed a low signal intensity, which is indicative of chronic rather than acute thrombosis. Therefore, oral anticoagulant treatment was not started. The patient recovered without major complications.

LEARNING POINTS

- Accurate diagnosis and treatment of aortic intraluminal thrombosis are of the utmost importance to prevent serious complications such as (peripheral) arterial embolic occlusion with resultant ischemia.

- Current imaging modalities do not allow for accurate distinction between acute and chronic thrombosis in the abdominal aorta. Hence, differentiating between stable and unstable thrombosis is challenging.

- The non-invasive magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging technique may be a valuable additional imaging test to establish a definitive diagnosis and treatment plan in patients with abdominal aortic thrombosis.

KEYWORDS

Aortic intraluminal thrombosis, magnetic resonance imaging, MR direct thrombus imaging, diagnosis, anticoagulation

INTRODUCTION

Aortic intraluminal thrombosis (ILT) commonly occurs in the presence of aortic pathology, such as aneurysmal disease, atherosclerotic plaque and/or dissection. Approximately 70-80% of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) develop a non-occlusive aortic ILT[1]. Accurate diagnosis and treatment of ILT are of the utmost importance to prevent serious complications such as (peripheral) arterial embolic occlusion with resultant ischemia[2]. We present what is, to the best of our knowledge, the first report of a patient in whom the non-invasive magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging (MRDTI) technique was used to determine whether an abdominal aortic thrombus was acute or chronic, and thus to guide antithrombotic management.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 43-year-old man was referred to our hospital reporting several months of abdominal discomfort. He was a heavy smoker with 30 pack/years. His medical history included an ischemic stroke, helicobacter pylori gastritis and severe hypertension complicated by cardiac hypertrophy. He was prescribed chlorthalidone, barnidipine, lisinopril, nebivolol, clopidogrel, simvastatin and ranitidine. His family history was remarkable for multiple aortic aneurysms and coronary artery disease in his father, who died at a young age of a ruptured aneurysm. His mother had been treated for systemic hypertension. On physical examination he was hypertensive with a blood pressure reading of 211/130 mmHg and a heart rate of 55 bpm. During auscultation of the abdomen a murmur was detected. Palpation of the abdomen was not painful. Peripheral pulsations were present in both arms and legs. Neurological examination was normal.

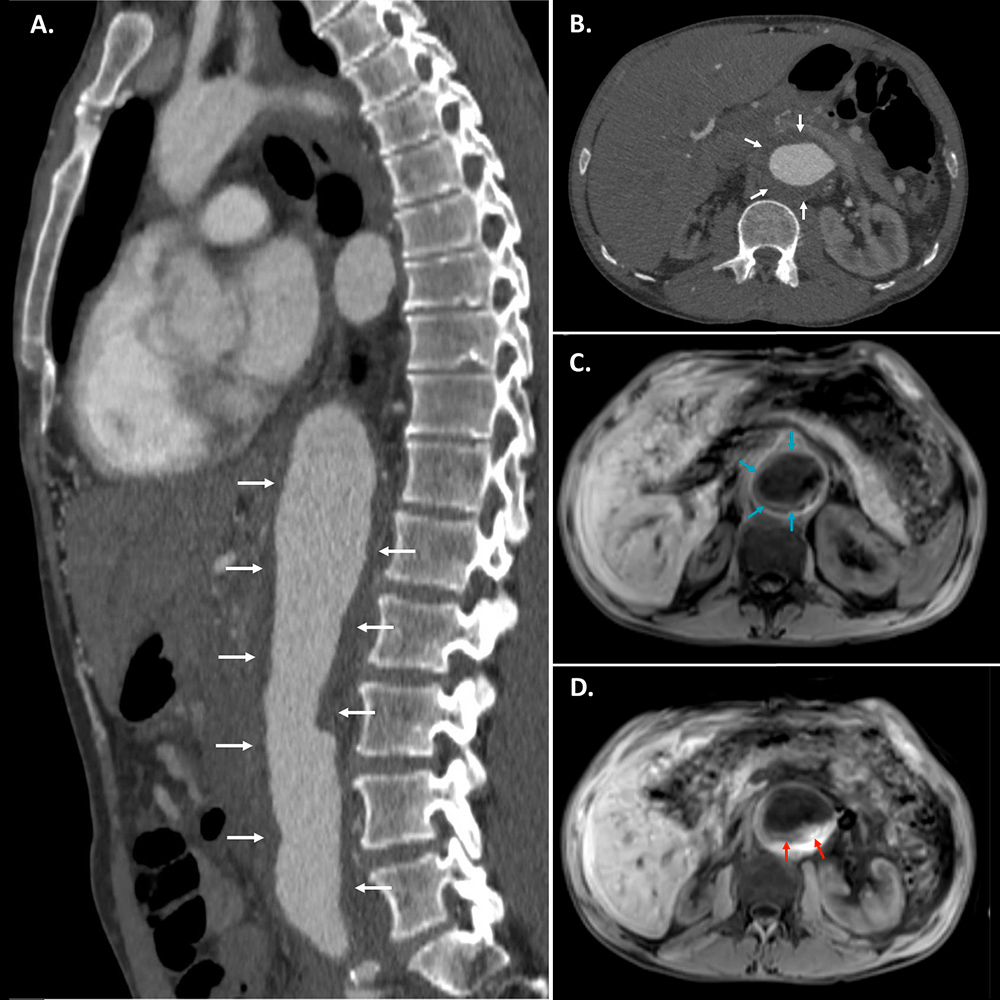

Laboratory results showed severe renal insufficiency with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 14mL/min and a creatinine level of 418 µmol/L. A CT angiography revealed a large suprarenal aortic aneurysm with diffuse circular atherosclerosis and extensive circumferential aortic wall thrombosis (Figs. 1A, 1B). The celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery and right renal artery were occluded and the right kidney was atrophic. The left renal artery was critically stenosed. The patient underwent a left renal artery percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), which was complicated by complete occlusion of the vessel. To rescue the left kidney and treat the abdominal angina a bifurcated Dacron bypass was made from the right external iliac to the left renal artery and common hepatic artery. Collateral flow via a well-developed gastroduodenal artery ensured adequate perfusion of the superior mesenteric arterial network. We were hesitant to initiate anticoagulant treatment because of the patient’s high bleeding risk due to the recent major surgery, severe hypertension and renal insufficiency. Therefore, an MRDTI scan was performed to assess the age of the thrombus; this showed a low signal intensity of the aortic thrombus, indicative of chronic rather than acute thrombosis (Fig. 1C). High signal intensity was found only in the aortic wall at the level of the left renal artery where the PTA had caused acute occlusion and bypass surgery had been performed (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. CT images after IV iodinated contrast and MRDTI images without contrast agent.

Figure 1A and 1B. Sagittal and axial CT images after IV contrast showing extensive wall thrombosis of the abdominal aorta (white arrows) which cannot be distinguished from the aortic wall.

Figure 1C. Axial MRDTI image showing chronic thrombosis (low signal intensity) in the aortic wall (blue arrows).

Figure 1D. Axial MRDTI image showing high signal intensity representing a recent thrombus in the aortic wall near the location of the PTA and rescue revascularization (red arrows).

Because no acute thrombosis was identified, anticoagulant treatment was not started and antiplatelet therapy was continued. Abdominal ultrasonography after the bypass surgery showed open bypasses. The patient’s renal function gradually improved, allowing him to be discharged from hospital in good health. In view of the premature aortic thrombosis in the presence of an AAA, genetic testing was performed but this was negative for both connective tissue disorders and for syndromic thoracic aortic aneurysm. The patient was kept under close outpatient surveillance because of chronic persistent renal insufficiency, characterized by an eGFR of 60 mL/min. In the first year after presentation, there were no thrombotic or bleeding complications.

DISCUSSION

Aortic ILT may lead to peripheral embolism resulting in occlusion of the distal arteries[3]. It is important to note that an acute aortic thrombosis (AAT) is a rare life-threatening event that may be caused by in situ thrombosis of an atherosclerotic aorta, a large saddle embolus to the aortic bifurcation, or occlusion of a previous surgical reconstruction[4]. Prompt management is indicated in the case of an AAT or an acute ischemic event caused by distal embolization[4] and may be considered in the presence of an unstable thrombus[1]. However, current imaging modalities do not allow accurate distinction between acute and chronic thrombosis. Differentiating between stable and unstable thrombi is therefore challenging.

MRDTI is a technique that allows a thrombus to be directly visualized without the use of a potentially toxic contrast agent. This method is based on the formation of methemoglobin in a fresh thrombus leading to shortening of the T1 signal on MRI[5]. It has been shown to accurately diagnose a first deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and to distinguish chronic thrombotic remains from acute recurrent DVT with a sensitivity of 95-100% and specificity of 100%[6,7]. Current studies are evaluating its diagnostic accuracy for unusual sites of venous thromboembolism, as seen for example in upper extremity DVT and splanchnic vein thrombosis (NTR 5738 and NTR 7061), where current imaging tests often cannot provide a definite diagnosis.

MRDTI may prove useful to overcome diagnostic challenges in the arterial system too, but the technique has not yet been extensively studied in this setting. In a preliminary study, 14 patients with acute limb ischemia were evaluated with MR angiography and MRDTI. MRDTI showed a positive signal in 11 (79%) patients. In 6 patients findings on thrombus length and occlusion were discrepant between MRDTI and MR angiography. Since recanalization with thrombolysis in these 6 patients was not achieved, it was suggested that the discrepancy reflected a difference between chronic arterial disease and superimposed acute thrombosis[8]. MRDTI has also been suggested to be useful in identifying complicated plaques in the carotid arteries and upper thoracic aorta in patients with cerebral vascular disease[9,10]. MRDTI has not yet been evaluated as a tool to guide anticoagulant treatment in abdominal aortic thrombosis. Because of the morbidity and mortality associated with complicated aortic ILT, accurate diagnosis of an unstable thrombus or differentiation between acute and chronic thrombosis remains crucial in selected patients.

We present the case of a patient who was diagnosed with AAA and extensive wall thrombosis in whom MRDTI made it possible to exclude acute and unstable thrombosis. MRDTI may therefore be a valuable additional imaging test to establish a definitive diagnosis and treatment plan in patients affected by abdominal aortic thrombosis with or without co-existing aortic pathology. More diagnostic studies are needed to support our findings.