ABSTRACT

Infectious purpura fulminans (PF) is a rare presentation of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) due to diffuse intravascular thrombosis and haemorrhagic infarction of the skin. PF can present in infancy/childhood or adulthood and usually presents as ecchymotic skin lesions, fever and hypotension. It is most commonly a consequence of sepsis related to Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae. Despite aggressive management of sepsis with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and conventional and nonconventional therapies, the condition still carries a mortality rate of 43%[1]. Streptococcus pneumoniae mostly presents with community-acquired pneumonia. We present a case of PF secondary to DIC related to Pneumococcal sepsis in an otherwise healthy and immunocompetent patient.

LEARNING POINTS

- Infectious purpura fulminans is a haematological emergency that demands early recognition and timely institution of therapy to prevent significant morbidity and mortality.

- A characteristic skin rash is a key diagnostic clue pointing to purpura fulminans, and should lead to prompt institution of therapy, as waiting for a skin biopsy result can delay the diagnosis and result in significant morbidity and mortality.

- Due to the lack of prospective data on management of the condition, various modalities, such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy and IVIG, still have questionable benefits. We therefore aim to expand knowledge of purpura fulminans management.

KEYWORDS

Purpura fulminans, sepsis, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, Streptococcus pneumoniae

CASE PRESENTATION

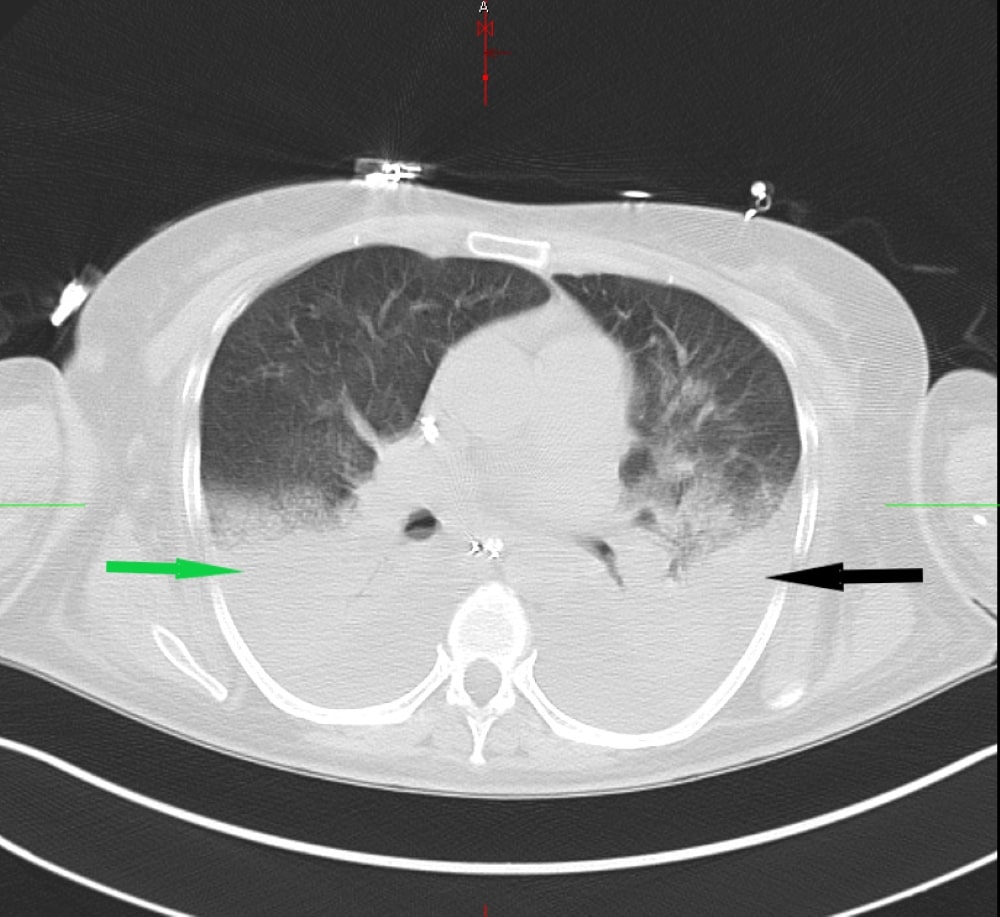

A previously healthy 56-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a two-day history of high-grade fever and shortness of breath. On physical examination, she was very ill-appearing, being hypotensive, tachycardic, tachypneic, and with mottled cold extremities. Chest radiogram and CT scan showed multilobar pneumonia (Fig. 1).

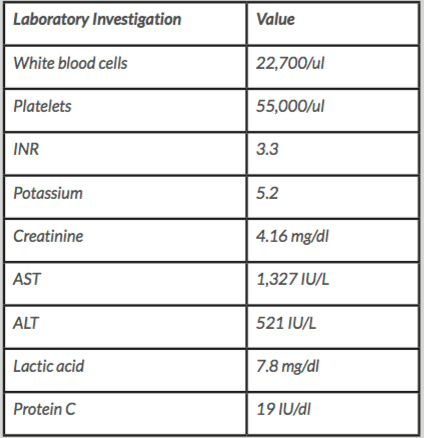

Due to her laboured breathing and hypotension, she was intubated and transferred to the medical Intensive care unit. Despite adequate fluid resuscitation, she required intravenous (IV) norepinephrine, vasopressin and dopamine for haemodynamic support. Blood cultures were obtained before starting IV vancomycin, ceftriaxone and azithromycin. The initial, pertinent laboratory workup is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealing multilobar consolidations in the right (green arrow) and left lung (black arrow)

Table 1. Pertinent laboratory values.

AST - aspartate transaminase, ALT - alanine transaminase, INR- international normalised ratio

The prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time were prolonged, and the fibrin degradation products were grossly elevated, suggesting disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC). Infectious workup was remarkable for positive urine Streptococcus pneumonia antigen; blood cultures grew Streptococcus pneumoniae. Over the next three days, the patient developed a diffuse petechial rash, which progressed from non-blanching purpuric ecchymotic skin lesions to flaccid bullae resulting in extensive skin sloughing off as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. (A) Ecchymotic and purpuric lesions on the left arm leading to substantial skin loss. (B) Bilateral purpuric rash extending the length of the lower extremities. (C) Bilateral gluteal purpuric lesions with gangrenous progression and sloughing of skin

A skin biopsy was performed, which revealed non-inflammatory vascular occlusion with skin necrosis, compatible with the clinical impression of purpura fulminans (PF). The patient received a 14-day course of broad-spectrum antibiotics, heparin drip and blood products. Due to inadequate response to the above therapies, hyperbaric oxygen therapy was instituted, which was stopped after eleven days as she showed no meaningful response. The patient developed anuric renal failure requiring haemodialysis. Bedside incisional fasciotomy did not reveal any evidence of muscle necrosis or compartment syndrome. The patient was transferred to the burns unit for further skincare as she showed 75% skin loss. In view of her prolonged hospital stay, dismal prognosis, and lack of meaningful recovery, a shared decision was reached by the family and treatment team to pursue comfort measures only.

DISCUSSION

Purpura fulminans (PF) is a life-threatening haematological emergency with rapidly progressive thrombotic sequelae, culminating in widespread haemorrhagic necrosis of the skin and DIC. It almost always involves relentless aberrant activation of the coagulation cascade, with an either hereditary or acquired predisposition. A deficit in the functioning of protein C (PC) is implicated in most cases of PF, however defects in other anticoagulant proteins, like protein S (PS) and anti-thrombin III, can also play a vital role in its pathogenesis. It is mostly encountered in the paediatric age group (neonates and children), although PF can potentially affect individuals of any age. The greater frequency of paediatric cases could be explained in terms of an early manifestation of an underlying hereditary PC defect, the frequent exposure to exanthematous viruses in this age group, and the fact that children have a newly active immune system.

The initial presentation consists of erythematous macules, rapidly progressing to areas of central cutaneous necrosis with surrounding erythema. The patches are painful and raised with dermal oedema and congestion; these symptoms are sometimes associated with the formation of vesicles or bullae, preceded by dermal capillary and postcapillary venular micro-thrombotic occlusion. Subsequently, full-thickness gangrenous necrosis ensues, which helps to differentiate these dark violaceous patches, histologically, from other types of purpuric lesions, namely immune thrombocytopenic purpura or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Henoch-Schonlein purpura may mimic PF lesions; however, it rarely produces necrotic skin lesions. Common presentations include non-blanching ecchymotic skin lesions, fever and hypotension, although hypotension is seen in only 51% of cases. DIC is present in 85% of patients, and hypofibrinogenaemia is documented in only 26%. Non-blanching purpuric lesions provide an early clue to the diagnosis and prompt initiation of therapy is necessary to prevent morbid sequalae. Although a skin biopsy is confirmatory, it can delay the diagnosis by up to a week. The syndrome is associated with more than 50% mortality secondary to multiple organ dysfunction, and it confers long-term morbidity.

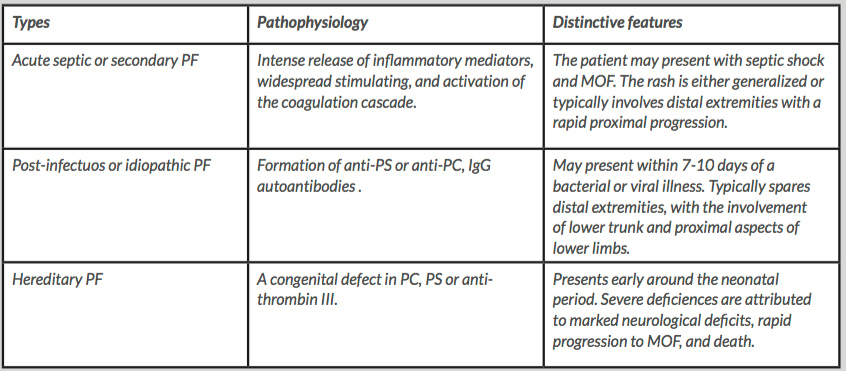

Based on aetiology, PF can be categorised into three distinct types: hereditary PF, acute septic or secondary PF, and post-infectious or idiopathic PF. Acute septic PF is linked to endotoxin and cytokine release as the primary trigger of the aberrant activation of the coagulation cascade. It typically affects the lower extremities with proximal progression, or presents a more diffuse distribution, involving the entire body. Post-infectious or idiopathic PF occurs within seven to ten days of a bacterial or viral infection. It is thought to be secondary to the formation of anti-PS autoantibodies, leading to an acquired deficiency of PS. Anti-PC autoantibodies are rarely detected in PF cases. The rash is typically distributed around the lower trunk, perineum, buttocks and thighs, characteristically sparing the distal extremities. Hereditary PF is associated with a congenital PC, PS or anti-thrombin III deficiency, presenting early in neonates, and showing a pattern of distribution similar to that seen in the post-infectious type. Severe PC deficiency is associated with considerable neurological insult, typically presenting with ischaemic optic atrophy and periventricular haemorrhagic infarction, with large vessel thrombosis and multi-organ failure. Table 2 summarises all three subtypes[2].

Table 2: Main pathophysiological components with concise description of clinical and physical findings in different types of PF

PF- purpura fulminans; PC- protein C; PS- protein S; IgG- immunoglobulin G; MOF- multi-organ failure

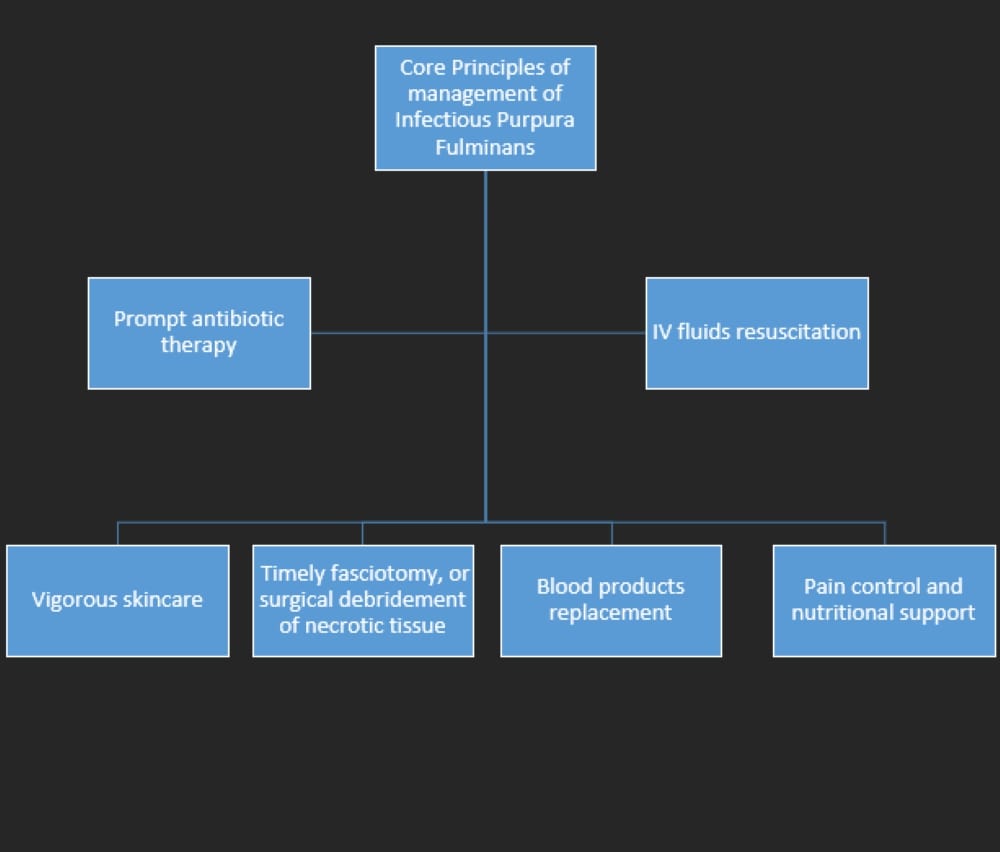

The aetiological spectrum reflects the close interplay between septic inflammatory mediators and the inherent deficiencies in the PC anticoagulant cascade. Management of infectious PF requires urgent intervention because of its precarious and rapidly progressive nature, especially in cases with an underlying septic nidus. Optimal management includes timely institution of IV fluid resuscitation and empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics with coverage against Neisseria meningitides and Streptococcus pneumoniae until specific culture reports are available. DIC results in depletion of coagulation factors, which often necessitates blood product transfusions, including fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate and vitamin K. The role of anticoagulant therapy in PF is controversial in the presence of underlying DIC, so stringent monitoring is warranted with anticoagulant use. However, anticoagulation therapy is mandated in cases with large vessel thrombotic occlusion[2]. Extensive skin and tissue necrosis resulting from dermal vascular thrombosis demands aggressive debridement of full-thickness necrotic tissue followed by skin grafting[3]. PC, PS and anti-thrombin III have been suggested as useful adjunct therapeutic options in the past as consumption of these anticoagulant proteins is implicated in the pathogenesis. Plasmapheresis and exchange transfusion may have a beneficial outcome in post-infectious or idiopathic PF, where clearance of antibodies can halt the disease progression[4]. High-dose IV corticosteroids are mainly limited to severe sepsis primarily due to meningococcal DIC-related adrenal haemorrhage or PF due to an underlying autoimmune aetiology such as antiphospholipid syndrome[4]. Although some studies have demonstrated beneficial effects of hyperbaric oxygen in the management of the condition, its use is questionable due to limited evidence and lack of recovery of affected tissues in most cases, as seen in our patient[5]. Nutritional support is also an integral part of treatment of patients with necrotising fasciitis and PF as it can expedite the healing process. The principles of PF management are summarised in Figure 3.