ABSTRACT

We present a case of a 56-year-old man with a history of episcleritis (left) and cluster headache (left) who had a penetrating trauma of the left eye leading to amaurosis 1 month previously. Since then, he developed multiple cranial neuropathy of the right side (V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI and XII cranial pairs). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an infiltrative lesion of the base of the skull which extended to the retropharyngeal and jugular space, which progressed to multiple leptomeningeal masses extending to the clivus, despite aggressive immunosuppression. Rebiopsy of 1 meningeal mass supported the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. The patient finally responded to high-dose prolonged infliximab therapy, with complete remission.

LEARNING POINTS

- Neurosarcoidosis can present as multiple cranial neuropathy, with extensive nerve involvement depending on the brain and meningeal lesions.

- Large leptomeningeal pseudotumoural granulomatous masses should be promptly biopsied and lead to aggressive immunosuppressive treatment.

- Immunosuppressant weaning should be carried out cautiously to avoid rebound worsening.

KEYWORDS

Neurosarcoidosis, cranial neuropathy, leptomeningeal mass

CASE DESCRIPTION

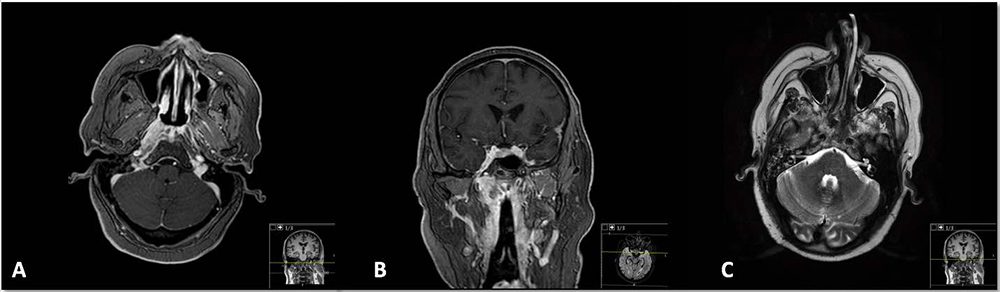

We present a case of a 56-year-old man, a cattle worker and former smoker (15 packs/year), with well-controlled arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. He had a 2-year history of multiple episodes of episcleritis (left eye) and left hemicranial cluster headache, for which he had been treated with systemic and topical corticosteroids and azathioprine (discontinued due to toxic hepatitis). One month before his referral to us, he had a left eye penetrating trauma (from a cow’s horn) leading to amaurosis. When we met him, the patient had right side otomastoiditis and hypoacusia, right peripheral facial palsy with ptosis, no right palate elevation, palsy and atrophy of the tongue, total dysphagia necessitating a nasogastric tube for feeding and an inability to elevate the right shoulder against resistance. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) found diffuse soft tissue thickening with imprecise limits extending to the clivus (Fig. 1A), with intense contrast enhancement extending to the retropharyngeal space and jugular region (Fig. 1B) along with inflammatory signs of the right mastoid and middle ear (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. (A) Diffuse soft tissue thickening with imprecise limits extending to the clivus; (B) intense diffuse contrast enhancement extending to the retropharyngeal space and jugular region; (C) inflammatory signs of the mastoid and middle ear secondary to Eustachian tube obstruction by soft tissue thickening

Complete blood cell count showed mild anaemia, an elevated sedimentation rate (52 mm/first hour), no evidence of kidney dysfunction or abnormalities of urinary sediment, a normal liver panel, normal serum and urinary calcium and normal angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed normal glucose and proteins, ACE 13 U/l, evidence of intrathecal production of IgG (9 oligoclonal bands of IgG with no correspondence in serum analysis), microbiologic analysis was sterile and testing for anti-neuronal antibodies was negative.

Serologies were unremarkable (HIV-1/2, HBV, HCV, EBV, CMV, HSV-1 and -2, varicella-zoster and Brucella). VDRL was also negative. Immunological assessment showed normal IgA, IgG, IgG4, IgM, C3 and C4. ANAs tested positive in a titre of 1/80, nucleolar pattern, and testing for ANCA, anti-SS-A, anti-SS-B, anti-centromere, anti-Scl-70, anti-PM/Scl, anti-dsDNA and anti-Smith was negative. Neck and cervical computed tomography (CT) angiography as well as thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT did not have relevant findings. 18F-FDG positron emission tomography showed metabolic activity in the retropharyngeal space, mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. The biopsy of retropharyngeal tissue showed chronic inflammatory infiltrate with lymphohistiocytic granulomas and no signs of lymphoma, neoplasm or vascular involvement, and negative microbiological results (bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial studies) were obtained.

Treatment was needed, and although no definitive diagnosis could be established, we assumed sarcoidosis-like granulomatous disease, with mainly neurological involvement with multiple cranial neuropathy, possible leptomeningitis and IgG intrathecal synthesis.

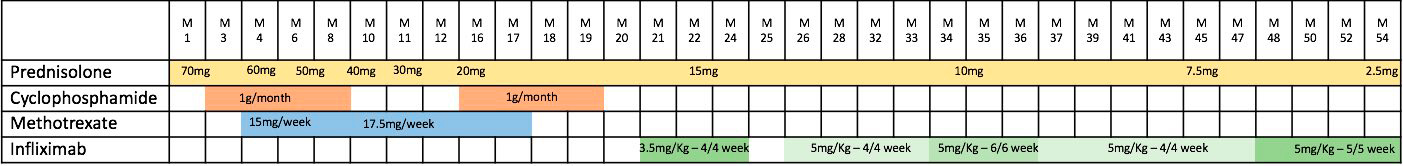

The patient started treatment with systemic prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) and intravenous (IV) cyclophosphamide 1 g monthly for 6 months (Table 1) with resolution of the deficits.

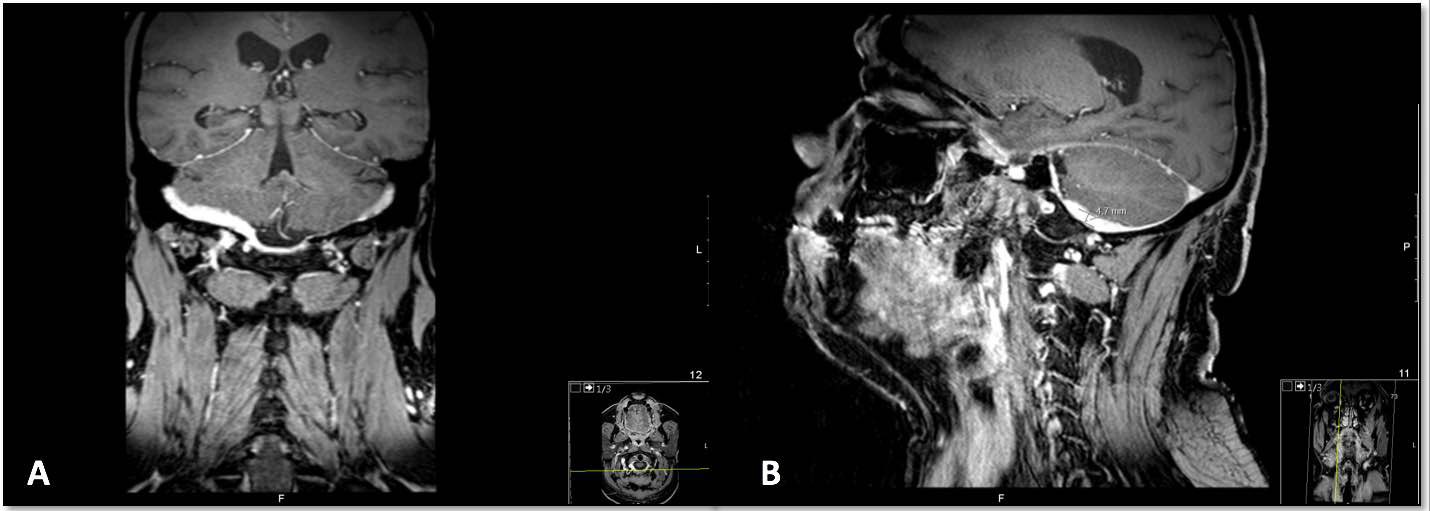

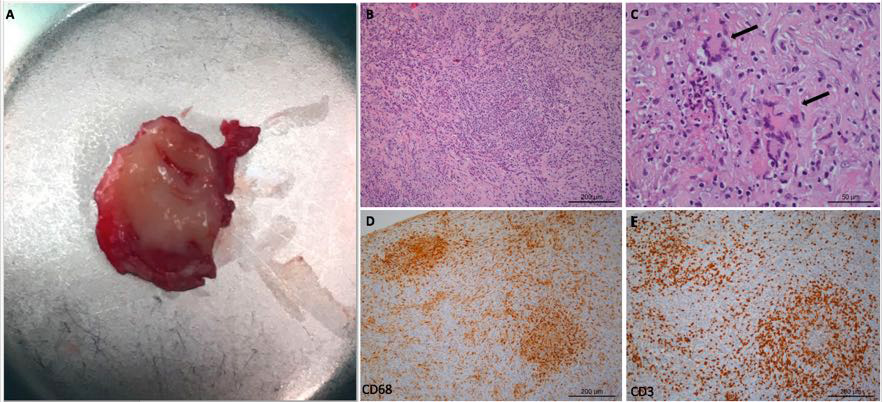

Despite maintenance therapy with oral methotrexate (17.5 mg/week) for 1 year, symptoms including severe headache and total dysphagia subsided after prednisolone withdrawal below 20 mg/day. IV cyclophosphamide was reintroduced but by the fourth monthly cycle, no response was noted. Infliximab was started at a dose of 3.5 mg/kg/cycle every 4 weeks with no response in the first 3 months and a new differential diagnosis work-up was made. MRI showed a leptomeningeal enhancement with extension to the occipital region and soft tissue mass through the lateral orbital cavities (Fig. 2) and a right suboccipital craniectomy was performed, for a dura mater biopsy: more than 20 elastic viscous masses (Fig. 3A) were found lining the internal skull base and 1 was removed. Histological examination confirmed granulomatous lesions with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, multinucleated giant cells and non-caseous necrosis, with no vasculitis and no acid-alcohol resistant bacilli (Fig. 3B–E), and there was a negative microbiologic work-up (bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi).

Figure 2. MRI with leptomeningeal enhancement with extension to the occipital region

Figure 3. (A) Macroscopic image of the leptomeningeal mass (diameter: approximately 2 cm) surgically removed for histologic examination. (B) Granulomatous lesion with lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic infiltrates; some PMN; non-caseous necrosis; (C) multinucleated giant cells (arrows); (D) predominance of histiocytes (CD68); (E) predominance of lymphocytes (CD3)

Infliximab dosage was increased to 5 mg/kg/cycle every 4 weeks and the clinical response was excellent, allowing the progressive reduction of prednisolone dosage and the total resolution of symptoms.

The patient experienced transitory symptomatic worsening when we tried to change infliximab frequency to every 6 weeks, and this resolved again with the 4-week interval for 1 year. The corticosteroid has been slowly weaned to 2.5 mg/day currently, and the patient is in complete clinical and MRI remission. He is now on infliximab every 5 weeks, for 6 months.

DISCUSSION

Sarcoidosis has neurological involvement in approximately 5 to 15% of cases. Neurosarcoidosis may manifest as a wide variety of non-specific symptoms, such as headache, dizziness, fatigue and fever, but cranial neuropathy is the most common neurologic manifestation of sarcoidosis and multiple cranial neuropathy with predominant unilateral involvement is often seen. This may be explained by the predilection for basilar meninges involvement with granulomatous infiltration, observed in almost 40% of neurological cases[1].

Brain tissue vulnerability and the low threshold for procedure-induced damage makes histopathological characterization of neurosarcoidosis less well known compared with other organ involvement, and in patients with neurological single organ manifestation, the diagnosis may be harder to confirm. In our patient, extensive investigation led to the exclusion of the majority of other differential diagnoses, mainly infectious or neoplastic aetiologies that could be life-threatening. A multidisciplinary approach encompassing otolaryngology, vascular surgery, neurology, neurosurgery, neuroradiology and internal medicine was crucial to guide this process. It seems to be in no doubt at the moment that the patient has neurosarcoidosis, with no other clinical involvement besides the central nervous system, but with 18F-FDG PET evidence of thoracic lymph node inflammation. In fact, in only 1% of cases, neurosarcoidosis can be isolated and limited to the nervous system[2]. Although cranial neuropathies are frequent, we did not find other reports with so many cranial nerves involved (V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI and XII). The trigeminal nerve (V) and vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII) are extremely rarely affected[3]. The presence of intrathecal IgG synthesis has also been reported in the literature[4].

Neurosarcoidosis treatment choices are based on expert opinion papers and small case series or case reports. The intensity of treatment depends on the severity of the manifestations: high steroids are the basis, but relapses are common and many patients will need additional induction and maintenance immunosuppressive therapy. Cyclophosphamide is traditionally used as a wide-spectrum immunosuppressant. Infliximab inhibits high TNF-α expression sarcoidosis granulomas with a good neurological penetration and has been used for refractory cases. A multi-institutional retrospective study with 66 patients led to recommendations supporting the use of TNF-α inhibitors in neurosarcoidosis, based on a favourable imaging and clinical response in three-quarters of patients treated with infliximab, although there were high relapse rates after discontinuation, consistent with other reports[5].

In our patient’s evolution, several steps can be discussed: was the initial cyclophosphamide 6-month treatment too short? If so, why was there no response on the second 4-month trial? Should we have chosen infliximab in the first place? It is clearer now that the dose of infliximab should have been 5 mg/kg/cycle every 4 weeks from the beginning. Since the patient is in remission for 2 years with a very low dose of corticosteroid, the main questions now are: how to wean it? And when to stop?