ABSTRACT

We report a case of acute viral pericarditis and cardiac tamponade in a patient with COVID-19 to highlight the associated treatment challenges, especially given the uncertainty associated with the safety of standard treatment. We also discuss complications associated with delayed diagnosis in patients who potentially may need mechanical ventilation.

LEARNING POINTS

- Large pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade should be considered in patients with COVID-19 who decompensate further after intubation and mechanical ventilation.

- The characteristics of pericardial effusion in patients with COVID-19 are described.

- A successful treatment approach for acute pericarditis in a patient with COVID-19 in light of differing opinions over the safety of NSAID use is described.

KEYWORDS

COVID-19, acute pericarditis, cardiac tamponade

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global pandemic and the result of infection by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. There is increased recognition of cardiac involvement in patients with COVID-19 as it confers a worse prognosis [2]. The most common cardiac complications include acute myocardial injury, arrhythmias, acute myocarditis and severe left ventricular dysfunction [1]. Conversely, reports of large pericardial effusions and associated life-threatening cardiac tamponade are rare [3]. We present a case of COVID-19-associated acute viral pericarditis complicated by large pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. To our knowledge, this is only the third report of cardiac tamponade in a patient with COVID-19 [3–5]. With observational studies suggesting that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids may exacerbate symptoms in patients with COVID-19, this case presented a therapeutic challenge in the management of acute pericarditis associated with large pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade [6].

CASE DESCRIPTION

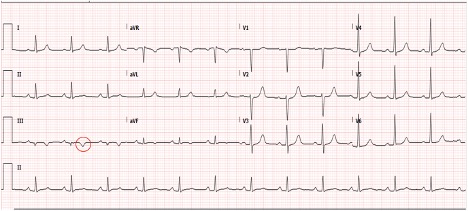

A 70-year-old West African female patient with a medical history of coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and a recent history of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) 2 weeks previously, treated with plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) to a small-size right posterolateral coronary artery, presented to the emergency room with chest pain, worsening dyspnoea, and myalgias for the last 3 days. Her presenting blood pressure (BP) was 124/59 mmHg, heart rate (HR) was 85 beats/minute, respiratory rate (RR) was 18 breaths/minute, temperature was 101.4°F and she was saturating at 93% on room air. An electrocardiogram (ECG) at presentation showed a normal sinus rhythm with T-wave inversions in the inferior leads similar to the patient’s baseline ECG (Fig. 1). The patient’s chest x-ray at presentation showed right basal atelectasis but no consolidation or effusion. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) performed 2 weeks earlier showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 55–60% with no pericardial effusion. Due to concern for COVID-19 infection in the setting of her respiratory symptoms and mild hypoxia, the patient was admitted to the general medicine ward for further management. A nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 infection returned positive.

Figure 1. Pulmonary CT images reveal multifocal bilateral ground-glass opacities with consolidation and a peripheral pattern, suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection

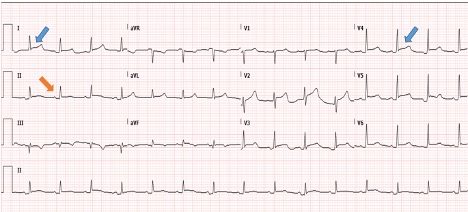

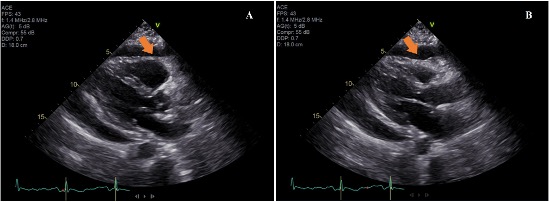

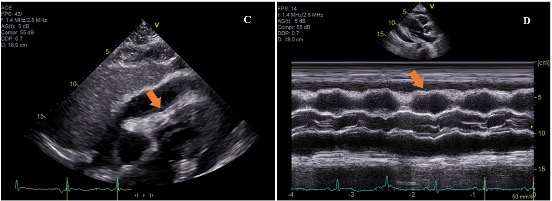

On day 2 of hospitalization, the patient complained of worsening chest pain. A repeat ECG showed diffuse 1-mm ST-segment elevations with PR depression suggestive of acute pericarditis (Fig. 2). At this time, the patient’s BP was 104/60 mmHg, HR was 70 beats/minute and RR was 27 breaths per minute, requiring 2 litres of oxygen by nasal cannula. A repeat chest x-ray showed an enlarged cardiac silhouette, bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and retro-cardiac opacities concerning for multi-focal pneumonia (Fig. 3). A TTE was obtained and showed an LVEF of 55–60%, a new large circumferential fibrinous pericardial effusion, right ventricular diastolic collapse, increased respiratory variation in peak E-wave mitral inflow velocity, a dilated inferior vena cava and septal bounce. These findings were consistent with tamponade physiology (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 2. Diffuse 1-mm ST-segment elevations (blue arrows) with PR depression (orange arrow) suggestive of acute pericarditis

Figure 3. Repeat chest x-ray showing an enlarged cardiac silhouette, bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and retro-cardiac opacities concerning for multi-focal pneumonia

Figure 4. Parasternal long axis view in systole (A) and diastole (B) on transthoracic echocardiography showing large circumferential pericardial effusion (arrows) and diastolic collapse of the right ventricle

Figure 5. Subcostal view (C) on transthoracic echocardiography showing diastolic collapse of the right ventricle (arrow). M-mode echocardiography (D) showing early diastolic collapse of the right ventricle (arrow)

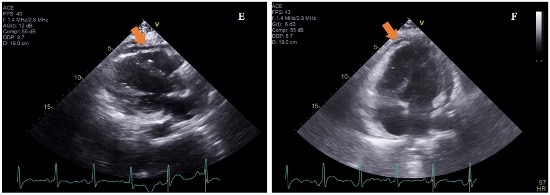

The patient progressively became more hypoxic and required urgent intubation and mechanical ventilation. After intubation, the patient became severely hypotensive with a BP of 71/48 mmHg, requiring vasopressor support with norepinephrine. Due to haemodynamic instability, the patient was urgently taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory where emergent pericardiocentesis was performed with removal of 460 ml of serosanguinous fluid. The opening pericardial pressure was 12 mmHg and the closing pressure was 2 mmHg. The patient’s vasopressor requirements decreased in the following hours. Pericardial fluid analysis showed a white cell count of 2,100/µl with polymorphonuclear predominance, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 3,086 U/l and protein of 5.3 g/dl. The fluid to serum protein ratio was 0.8 and fluid to serum LDH ratio was 3.0. Pericardial fluid Gram stain, bacterial, mycobacterial and fungal cultures were all negative. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 on pericardial fluid is not available at our centre. Pericardial fluid cytology was negative for any malignant or suspicious cells. The pericardial effusion was judged to be secondary to SARS-CoV-2-related acute pericarditis. Owing to reports of NSAIDs and corticosteroids potentially worsening symptoms in patients with COVID-19, colchicine was initiated. The patient’s repeat TTE showed an LVEF of 55–60% and small residual fibrinous pericardial effusion (Fig. 6). The patient was eventually extubated and her pericardial effusion remained stable on serial TTEs.

Figure 6. Images taken after pericardiocentesis (E and F), depicting improvement in the size of the effusion (arrows)

DISCUSSION

Cardiovascular comorbidities are common in patients with COVID-19 and these patients are at higher risk of morbidity and death [1]. Furthermore, patients with COVID-19 present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges because respiratory and cardiac pathologies frequently co-exist and their clinical presentation may be similar [1]. Even though pericardial involvement is a rare extra-pulmonary manifestation of COVID-19, it should be kept in mind as intubation and positive pressure ventilation (PPV) can have deleterious haemodynamic effects in patients with cardiac tamponade [4, 7]. There has been a lot of uncertainty in proceeding with procedures in cardiac catheterization laboratories in light of the need to balance staff exposure and patient benefit [8]. Since many patients with COVID-19 warrant intubation and mechanical ventilation, it might be reasonable to consider early controlled invasive management of large pericardial effusions to avoid haemodynamic decompensation and the need for emergent pericardiocentesis.

High-dose aspirin and NSAIDS are the mainstay of therapy for acute pericarditis [9]. Other treatment options include colchicine [10]. Corticosteroids are reserved for cases with a contraindication or failure of first-line therapies [10]. With early anecdotal evidence linking NSAIDs and corticosteroids with a worsening clinical condition in patients with COVID-19, there have been recommendations against the use of these agents [6]. In our case and given the recent NSTEMI, both NSAIDs and corticosteroids should be avoided when treating pericarditis [11]. The recommendation for patients with myocardial infarction and acute pericarditis is to start high-dose aspirin [11]. This creates management difficulties in patients with COVID-19 and acute pericarditis due to the uncertainty of high-dose aspirin safety in those patients. The literature to date has not provided conclusive evidence for or against the use of high-dose aspirin [6]. The concerns were primarily regarding the use of ibuprofen and no scientific data are available linking worsening of COVID-19 with aspirin or other NSAIDs [6]. According to the recommendations from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), NSAIDs can be used when clinically indicated [9, 12]. Similarly, NSAIDs being used for chronic conditions should not be discontinued in patients with COVID-19 [9, 12]. Although traditionally colchicine is added to NSAIDs for the treatment of acute viral pericarditis, we used it as monotherapy in our patient and it was well tolerated [9]. Dabbagh et al. in their case of COVID-19 and cardiac tamponade report the successful use of the combination of corticosteroids and colchicine and it was well tolerated [4]. However, this was not an option in our patient given the recent myocardial infarction [11]. We carried out a literature search and existing data do not provide definite evidence against the use of high- or low-dose aspirin when clinically indicated in patients with COVID-19 [6, 11]. Until we have more evidence, the decision on the use of high-dose aspirin in the management of patients with COVID-19-related acute pericarditis should be individualized [6, 9].

Since this is only the third report of cardiac tamponade in a patient with active COVID-19, this case also adds information about the characteristics of the pericardial fluid in patients with COVID-19 [3, 4]. Pericardial fluid analysis in our patient and in one case previously described showed a largely exudative effusion with a high polymorphonuclear cell count, high protein and LDH levels [4]. There is no set of laboratory parameters to help distinguish COVID-19-related pericardial effusion from other aetiologies. Until polymerase chain reaction testing for SARS-CoV-2 on pericardial fluid becomes more widely available, we suggest complete biochemical, bacteriological and cytological analysis of pericardial fluid to rule out other aetiologies of pericardial effusion.