ABSTRACT

Thromboembolic disease is strongly associated with, or even an integral part of, COVID-19 pneumonia. Indeed, endothelial/microvascular damage to pulmonary capillaries seems to be the main trigger of the pneumonia. Here we report a case of pulmonary embolism in a COVID-19 patient with an atypical clinical presentation. Blood gas analysis and lung ultrasound allowed the correct diagnosis to be reached.

LEARNING POINTS

- COVID-19 pneumonia is associated with cardiovascular complications and pulmonary embolisms.

- Lung ultrasound can aid diagnosis by visualizing small peripheral pulmonary embolisms.

KEYWORDS

COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, pulmonary embolism, ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) infection is associated with cardiovascular disease, either by increasing the risk of death in patients with pre-existing cardiac disease or directly by causing COVID-19 cardiovascular complications such as acute myocardial injury, arrhythmias and pulmonary embolisms. The inflammatory response, cytokine storm, and lung injury related to COVID-19 are responsible for an increased risk of thrombosis [1, 2]. Pathological haemostatic changes are often detected early in COVID-19 patients, and high D-dimer values are the most frequent abnormality [3]. Here we discuss the case of a 50-year-old man reporting vomiting, fever and loss of appetite for a week with no signs of deep venous thrombosis, who received a final diagnosis of respiratory failure due to pulmonary embolism.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 50-year-old man was referred to our emergency department for vomiting, fever and loss of appetite for a week. He also reported cough and atypical chest pain towards the top of his sternum. Asthenia and arthromyalgia were also present. He denied contact with anybody suspicious for COVID-19. His vital parameters were: blood pressure 135/70 mmHg, heart rate 74 bpm, respiratory rate 14 breaths/min, and peripheral oxygen saturation 96%.

Blood gas analysis revealed: pH 7.4, pCO2 40 mmHg, pO2 73.9 mmHg, P/F 352, and alveolar–arterial gradient 26 (expected value for age: 17). The electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with a mean heart rate of 70 bpm. The patient’s medical history was characterized by depression and tobacco consumption, treated with paroxetine, olanzapine, trazodone and lorazepam.

On physical examination, the patient was alert and collaborative, with no neurological deficits. The abdomen was painless and bowel function was regular. Lung auscultation revealed a slightly reduced vesicular murmur in the right basal region. Heart sounds were normal. There was no oedema in the lower limbs or pain on palpation.

Blood examination revealed: white blood cells (WBC) 7700×109/l, neutrophils 5.2×109/l, lymphocytes 1.8×109/l, D-dimer 1.5 mg/l, INR 1.0, aPTT ratio <0.8, platelets 202×109/l, LDH 468 U/l, AST 83 U/l, ALT 30 U/l, C-reactive protein 1.55 mg/dl, procalcitonin 0.2 ng/ml and creatinine 0.9 mg/dl.

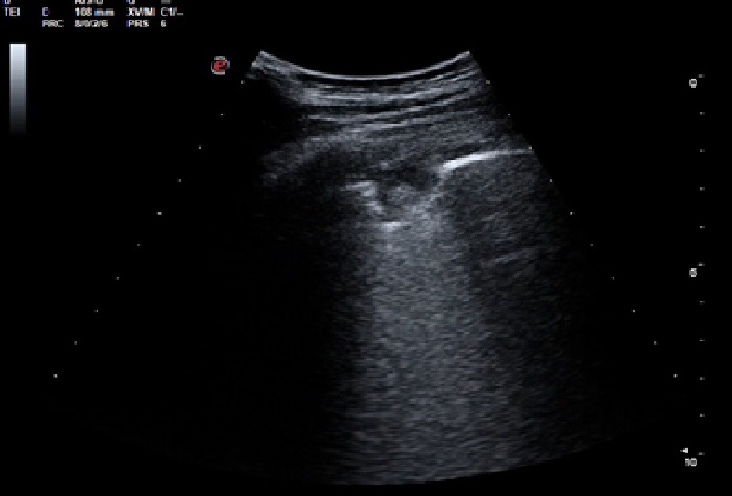

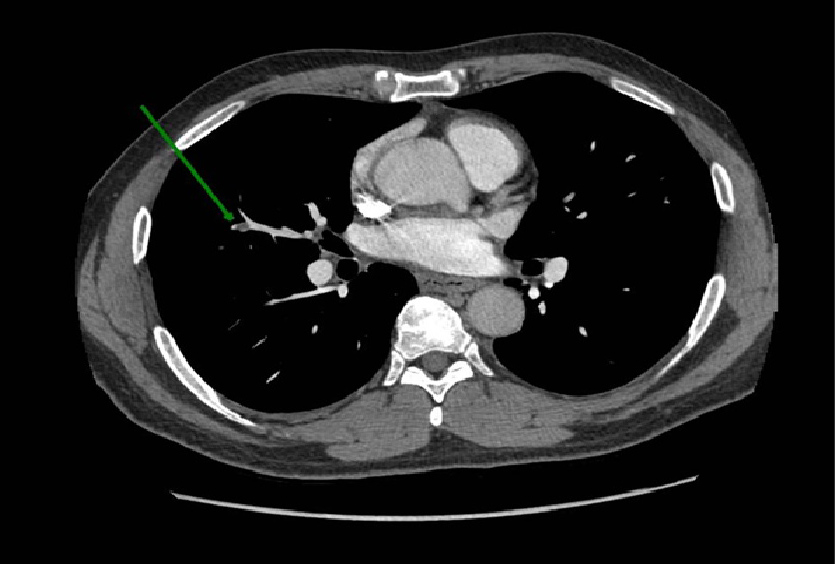

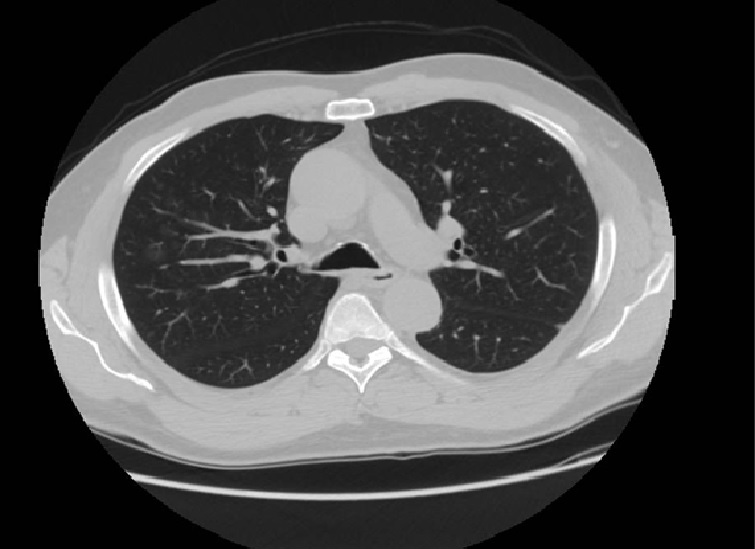

Lung ultrasound showed minimum pleural effusion in the right basal field, while a round pleural-based consolidation was present with some B lines in the right field (Fig. 1). A chest CT scan was therefore performed and showed filling defects compatible with non-occlusive thromboembolism at the level of the apico-dorsal segmental branch of the upper right lobe and of the subsegmental branches of all right lobes and of lower lung lobes on the left. There was also complete occlusion of a peripheral subsegmental vessel to the dorsal segment of the lower right lobe (Figs. 2 and 3). Small ground-glass opacities were evidenced in the parailary lung field near the upper right lobe. A modest pleural film was seen on the right (Fig. 4). There was no mediastinal lymphadenomegaly. The nasopharyngeal swab was positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection. A subsequent angiogram with echo colour Doppler did not reveal any venous thrombosis in the limbs. The patient underwent anticoagulant therapy.

Figure 1. Ultrasound showing pulmonary embolisms, represented as hypoechoic, wedge-shaped, pleural-based parenchymal lesions. A central echo can often be seen within the lesion. Localised effusion, basal effusion or both are also sometimes present

Figure 2. Angio-CT scan showing filling defects at the level of the apico-dorsal segmental branch of the upper right lobe

Figure 3. Angio-CT scan showing complete occlusion of a peripheral subsegmental vessel to the dorsal segment of the lower right lobe

Figure 4. HRCT scan showing small ground-glass opacities in the parailary lung field near the upper right lobe

DISCUSSION

The final diagnosis was bilateral pulmonary embolism in a patient positive for COVID-19. Reports in the literature have shown that thromboembolic disease is strongly associated with, or even an integral part of, COVID-19 pneumonia. Indeed, endothelial/microvascular damage to pulmonary capillaries seems to be the main trigger for pneumonia. Virus binding to pneumocytes via the ACE-2 receptor causes pneumocytic damage with activation of the inflammatory response and release of prothrombotic factors [3].

The most surprising finding in our case was the lack of the classic clinical signs of thromboembolic disease: the patient had no oedema or pain in the lower limbs, no history of trauma or immobilization, and no prothrombotic or active neoplastic disease, resulting in a negative pretest probability score (Well’s score = 0). Moreover, there were no ancillary signs such as a tachycardia.

Our patient had several findings suspicious for COVID-19. The P/F value and an increased alveolar–arterial gradient suggested mild respiratory failure. Also, lung ultrasound showed mild pleural effusion and consolidation with a specific morphology: small peripheral pulmonary embolisms characterized by lesions with a clear morphology (no pneumonia shred sign), with a clear pleural base, often round or triangular shaped, with few or no B lines [4, 5]. In addition, D-dimer blood levels were above the upper limit of normal.

These findings led us to request higher level imaging, which confirmed the clinical suspicion. Our clinical case demonstrates how thromboembolic disease can manifest very differently in a patient with SARS-CoV-2: rather than peripheral venous thrombosis inducing a pulmonary embolism, the virus and inflammatory response induce primary disease of the pulmonary circulation. This raises clear diagnostic concerns, since the normal procedure for diagnosing thromboembolic disease does not seem to be valid.

In the context of large-scale screening for COVID-19, simple, low-cost and repeatable methods such as blood gas analysis and lung ultrasound can be valuable. First, evaluation of gas exchange data (P/F and alveolar–arterial gradient) is useful for assessing respiratory function. Second, ultrasound can provide excellent diagnostic accuracy by visualizing even small peripheral pulmonary infarcts, albeit with the known limitations as regards deep lesions.