ABSTRACT

Emphysematous gastritis is a rare but fatal variant of gastritis. It is caused by gastric wall invasion by gas-forming organisms. It follows disruption of gastric mucosal integrity by a variety of factors, most commonly caustic ingestion and alcohol abuse. Patients typically present with abdominal symptoms with features of septic shock. Emphysematous gastritis carries a high mortality rate warranting early intervention with supportive measures and broad-spectrum antibiotics. It is essential to consider this rare entity in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with abdominal pain as timely intervention is crucial for survival.

LEARNING POINTS

- Emphysematous gastritis is rare but important to keep in mind when evaluating patients with acute abdominal pain.

- Emphysematous gastritis is a serious condition which has a high mortality rate if not diagnosed early.

KEYWORDS

Emphysematous gastritis, chronic abdominal pain, chronic mesenteric ischemia

INTRODUCTION

Emphysematous gastritis is a lethal and rare form of phlegmonous gastritis caused by gastric invasion by a gas-forming micro-organism within the wall of the stomach [1]. It was first described clinicopathologically by Fraenkel in 1889 and radiologically by Weens in 1946 [2]. The clinical presentation of emphysematous gastritis can be quite dramatic with abdominal pain, sepsis and shock, and carries a high mortality rate [2]. The bacterial invasion occurs when there is disruption of mucosal integrity, which can be due to multiple risk factors [3]. Radiological studies play an essential role in the diagnosis of this condition [2].

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 64-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease, five-vessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery and subsequent percutaneous coronary intervention, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus, presented to the hospital with a 4-month history of worsening left lower quadrant abdominal pain and diarrhoea. The patient had been admitted 2 weeks previously for the same complaints. At that time, work-up including gastrointestinal polymerase chain reaction, computerized tomography (CT) scanning of his abdomen and pelvis, and colonoscopy were inconclusive.

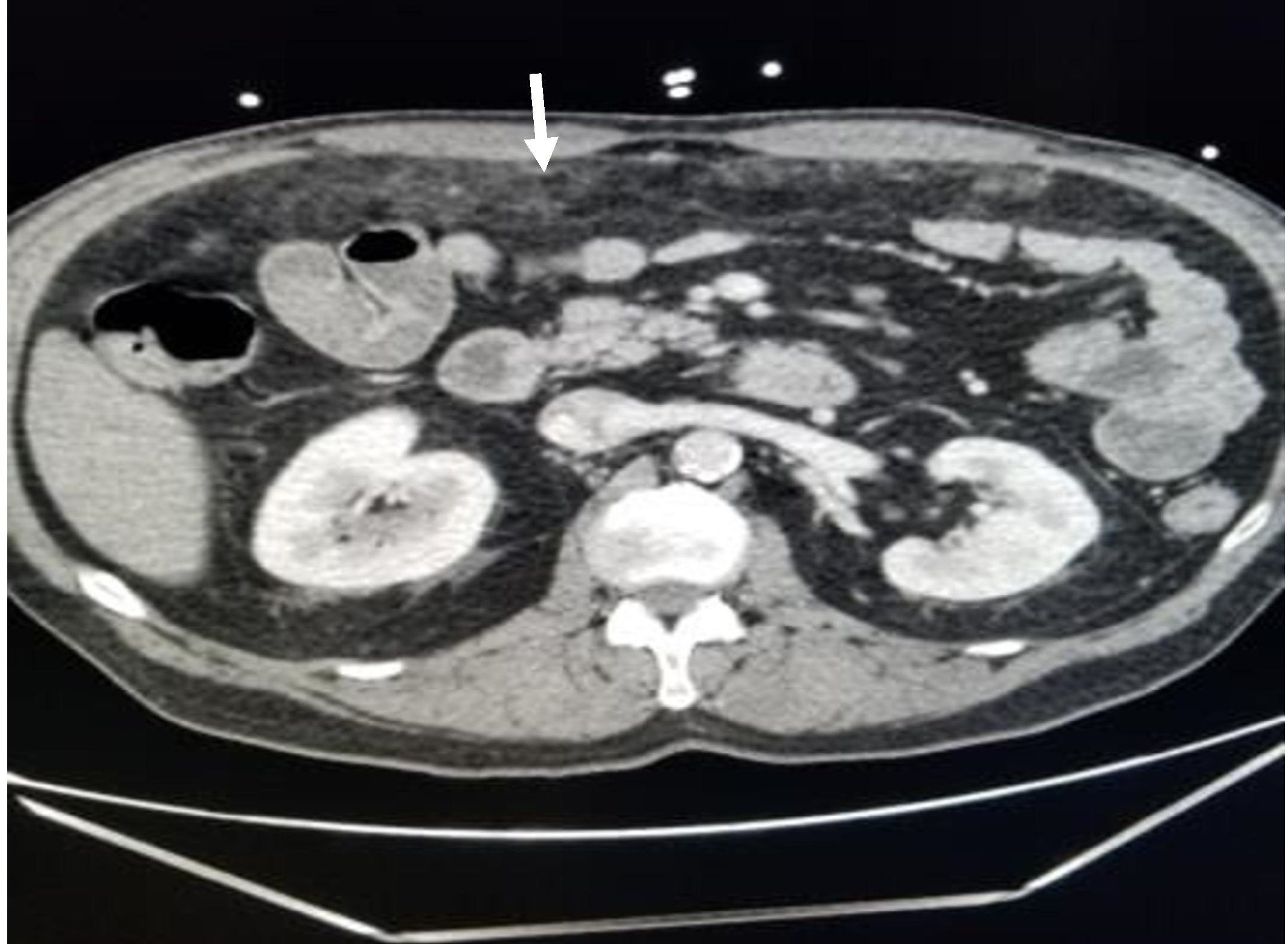

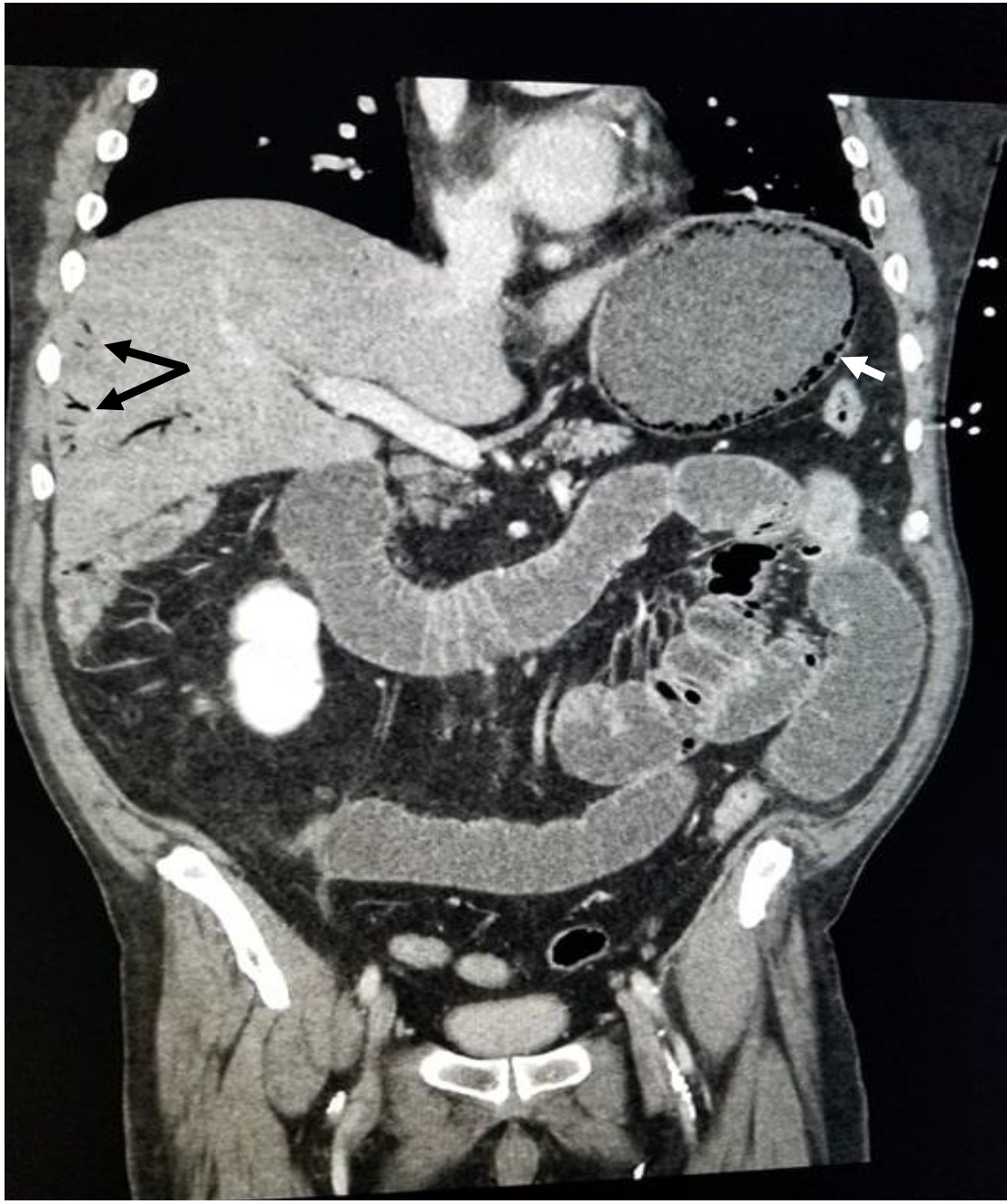

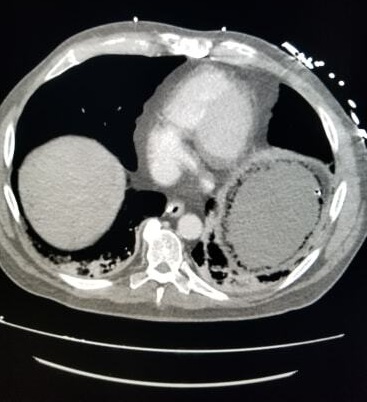

On the second presentation to the same hospital, the pain was diffuse and more severe. It worsened with oral intake and improved with bowel movements. The pain was associated with non-bloody diarrhoea, nausea, non-bilious/non-bloody emesis, and a 70-pound weight loss. On examination, the patient was afebrile, heart rate was 79 beats per minute, and blood pressure was 159 mmHg/68 mmHg. His abdomen was diffusely tender, worse in the mid-epigastric region and left quadrants, with associated guarding, rebound tenderness, and hypoactive bowel sounds. Laboratory results included a white blood cell count of 21,000/µl with 7.3% bands. A repeat gastrointestinal polymerase chain reaction was negative. CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed extensive atherosclerotic vascular disease with focal stenosis of the celiac and superior mesenteric artery, small bowel loop dilatation, and omental thickening (Figs. 1–3). Imaging was repeated 24 hours later due to worsening pain and revealed gastric pneumatosis, venous gas surrounding the stomach, and portal venous gas (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 1. Sagittal section view of the CT angiogram of the abdomen showing narrowing of the celiac artery (blue arrow). Other findings include extensive calcification which is seen as multiple white plaques along the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery and aorta

Figure 2. Multiplanar reformation CT scan of the abdomen in sagittal section, showing stenosis in the celiac artery and distal branch of the superior mesenteric artery (blue and white arrows, respectively). It also shows calcification plaques in the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery and aorta (black arrows)

Figure 3. Cross-sectional view of the CT scan of the abdomen showing omental thickening (white arrow)

Figure 4. Coronal section view of the CT scan of the abdomen showing gas within the wall of the stomach (white arrow) and portal vein gas (black arrow)

Figure 5. Cross-sectional view of the CT scan of the abdomen showing gas within the wall of the stomach circumferentially

The patient was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and underwent nasogastric tube placement for gastric decompression and bowel rest. Subsequently, he underwent stenting of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries by vascular surgery and had marked improvement in his pain. One week later, the patient was tolerating an oral diet and his bowel function had returned. He was discharged after completing 10 days of intravenous antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Amongst all hollow organs, the stomach is the least likely to be affected by gas-forming organisms, and so emphysematous gastritis is a rare diagnosis [4]. An ample blood supply, intact gastric mucosa and acidic environment help to prevent gastric infections. Factors that alter gastric integrity can predispose to emphysematous gastritis, including the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, malignancy, gastroenteritis, recent abdominal surgery, rheumatic disease, corticosteroid use, and gastric infarction [1–4]. When altered, the gastric mucosa can be invaded by gas-forming organisms, most commonly Streptococci, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter species, Clostridium welchii, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Proteus species, and lead to emphysematous gastritis [1–4]. Candida species and Mucor species have also been identified as possible infectious causes of emphysematous gastritis [1, 2]. Patients with the condition can present with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, and rapidly decompensate with sepsis, gastrointestinal haemorrhage and shock [1, 2, 4, 5].

With the non-specific clinical presentation and laboratory results, diagnostic imaging is imperative in making a diagnosis of emphysematous gastritis [4, 5]. Although gastric wall gas can be identified on plain radiograph, CT scanning remains the modality of choice in achieving the correct diagnosis [2, 4, 5]. Common CT scan findings include stomach distention, thickened mucosal folds, intramural gas, portal vein gas and pneumoperitoneum [2, 4, 5]. Radiologically, emphysematous gastritis can mimic gastric emphysema, a more benign, non-infectious type of gastric pneumatosis that can occur after trauma, endoscopy or vomiting, or intestinal obstruction.

Patients with gastric emphysema and emphysematous gastritis present with abdominal symptoms, but those with emphysematous gastritis present with more severe abdominal pain, peritoneal signs and sepsis [2].

The mortality rate of emphysematous gastritis is estimated to be 60–80%, so early diagnosis and treatment is crucial [2, 4]. Therapeutic interventions involve treatment of the underlying factors contributing to the development of emphysematous gastritis, early initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics with activity against gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria, intravenous fluid administration, electrolyte imbalance correction, and nutritional support [2, 4, 5]. Surgery is best delayed until the resolution of sepsis, unless there is another indication, as the mortality rate can be as high as 21% [2, 4, 5]. Surgery, even when delayed, has also been associated with complications including anastomosis failure, stricture and fistula formation [4].

In conclusion, although emphysematous gastritis is a rare form of gastritis, early recognition and treatment is imperative given its high mortality rate.