ABSTRACT

Acromegaly is characterized by excess skin and soft tissue growth due to increased growth hormone (GH) levels. Patients with similar physical findings but without somatotroph axis abnormalities are considered to have pseudoacromegaly. The list of pseudoacromegaly differential diagnoses is long. It may be caused by several congenital and acquired conditions and diagnosis can be challenging due to its rarity and occasional overlapping of some of these conditions. The presence of a pituitary tumour in such cases may lead to a misdiagnosis of acromegaly, and thus, biochemical evaluation is key. Here, we present a case of pseudoacromegaly with an acromegaloid phenotype, normal IGF levels, a supressed GH response to an oral glucose tolerance test, moderate insulin resistance and non-functioning pituitary microadenoma.

LEARNING POINTS

- There are several conditions that present with clinical aspects of acromegaly or gigantism but without growth hormone (GH) excess. Such cases are described as "pseudoacromegaly" or "acromegaloidism".

- In cases of excessive soft tissue growth with normal GH levels, other growth promotors (for example, thyroid hormone, sex hormones, insulin and others) should be taken into consideration.

- Biochemical confirmation of GH excess in patients presenting with clinical features of acromegaly and pituitary adenoma should always be considered to avoid unnecessary surgeries.

KEYWORDS

Pituitary, growth factors, acromegaly, pseudoacromegaly, adenoma

INTRODUCTION

Acromegaloidism or pseudoacromegaly was first defined by R.B. Mims in the 1970s as a body condition resembling acromegaly but not due to a pituitary or hypothalamic disorder. Although it is difficult to distinguish these 2 distinct phenomena from each other by clinical features alone, patients with pseudoacromegaly usually have normal growth hormone (GH) and somatomedin levels at baseline and in dynamic tests[1]. This finding has prompted investigators to look for overgrowth promotors other than GH/IGF1. In the literature, there are many reported conditions that give rise to pseudoacromegaly by several congenital and acquired mechanisms, including Sotos syndrome, congenital generalized lipodystrophy, pachydermoperiostosis, severe insulin resistance, long-standing undiagnosed hypothyroidism and drugs such as minoxidil. To our knowledge, few cases have been reported on pseudoacromegaly with coexisting non-functioning pituitary adenoma [2]. Here, we describe a case with this unusual presentation.

CASE DESCRIPTION

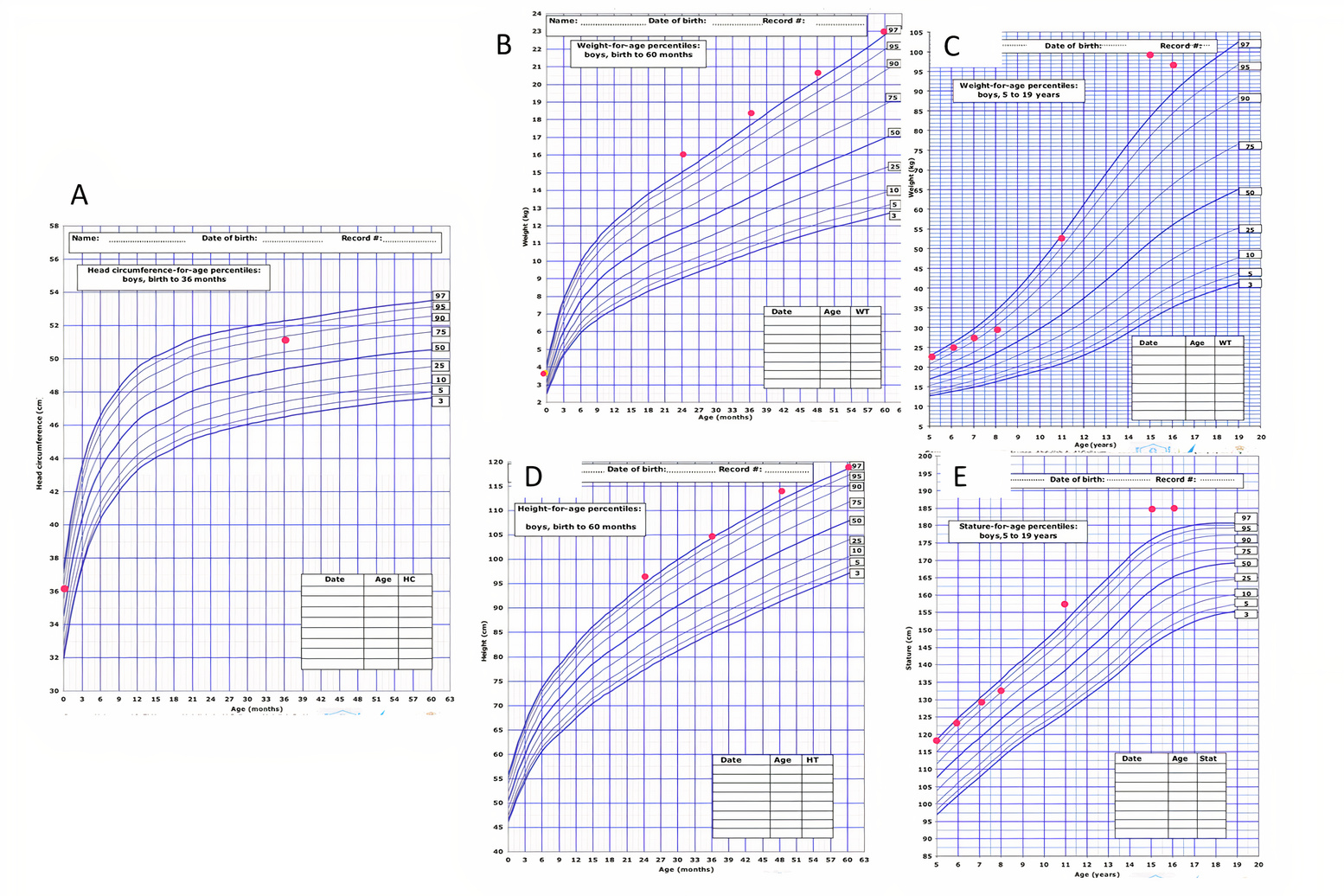

In December 2018, a 16-year-old boy was referred from the neurosurgery clinic to our adult endocrinology clinic to rule out acromegaly. His background medical problems included a posterior fossa arachnoid cyst and multiple renal cysts since birth with no clinical consequences. Further questioning revealed that he was born full-term by caesarean section due to transverse lie and possible macrocephaly, his birth weight was 3.7 kg and head circumference was 36 cm. His early developmental milestones were reported to be within normal limits except for speech delay until the age of 3 years, attributed to a large tongue and tongue tie, and delayed sphincter control. He still had difficulties in articulation. His parents reported behavioural changes early in life in the form of disobedience and being aggressive, which required behavioural therapy with considerable subsequent improvement. He still had learning difficulties with a short attention span. His performance at school was poor. His family noticed different facial features to their other offspring since birth, with rapidly increasing height and frequent changing of clothes and shoe sizes since the age of 6 years (see growth charts in Fig. 1). The patient entered puberty at 15 years old. He still had chronic left-sided headache, excessive sweating and chewing difficulties. No arthralgia, weakness or visual changes were noted. The parents were consanguineous. There was no family history of the same presentation. Examination revealed height 185 cm (above 97th percentile), weight 91.9 kg (above 97th percentile), BMI 26.8 kg/m2. The patient was normotensive, had coarse facial features, a long face, frontal bossing, orbital hypertelorism, acne, prognathism, macroglossia, tongue tie, sweaty skin, excessive hair and acral overgrowth (Fig. 2). There was no evidence of seborrhoea, skin tags, acanthosis nigricans, goitre, skeletal deformities, arthropathy or compressive neuropathies. The visual fields as assessed by a confrontation method were normal. The patient had normally developed secondary sexual characteristics.

Figure 1. The patient’s growth charts: (A) head circumference for age percentile from birth to 36 months, (B) weight for age percentile from birth to 60 months, (C) weight for age percentile from 5 to 16 years, (D) height for age percentile from 24 to 60 months, (E) height for age percentile from 5 to 16 years

Figure 2. Showing macroglossia, prominent supraorbital ridges, orbital hypertelorism, prognathism, tongue tie, acne, acral enlargement and hypertrichosis

Other systemic examination gave normal findings. Biochemical evaluation showed GH 0.058 (0–5 ng/ml), IGF1 489.3, 388.2, 435.7 at different occasions (150–555 ng/ml, population-based reference range), GH 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 120 minutes post-OGTT was 0.266, 0.230, 0.158, respectively (N<0.4 ng/ml), TSH 1.61 (0.35–4.94 mIU/l), FT4 13.7 (9–19 pmol/l), prolactin 17.57 (3.46–19.4 ng/ml), LH 1.97 IU/l, testosterone 10.96 (1.63–34 nmol/l), insulin 20.3 (0.87–20.44 µU/ml), FBG 5.2 mmol/l, 2-h BG during OGTT 9.4 mmol/l, ACTH 32.33 (7–50 pg/ml), morning cortisol 445.6 nmol/l, cholesterol 2.9, LDL 1.72, TG 0.66, HDL 1.0, A1C 5.1 and a normal renal function test, liver function test and bone panel. The calculated insulin resistance based on HOMA-IR was elevated at 4.69 (N 1–4), indicating early insulin resistance. Pituitary MRI showed a stable, previously seen, posterior fossa arachnoid cyst measuring 24 mm, and a new 3 mm right pituitary gland microadenoma (Fig. 3). The patient’s chromosomal analysis at the age of 2 years showed karyotype 46,XY with no numerical or structural chromosome abnormalities. To date, there has been no indication for pituitary surgery in our patient and he has been followed as per recommendations for micro-incidentaloma cases.

Figure 3. Pituitary MRI showing the microadenoma

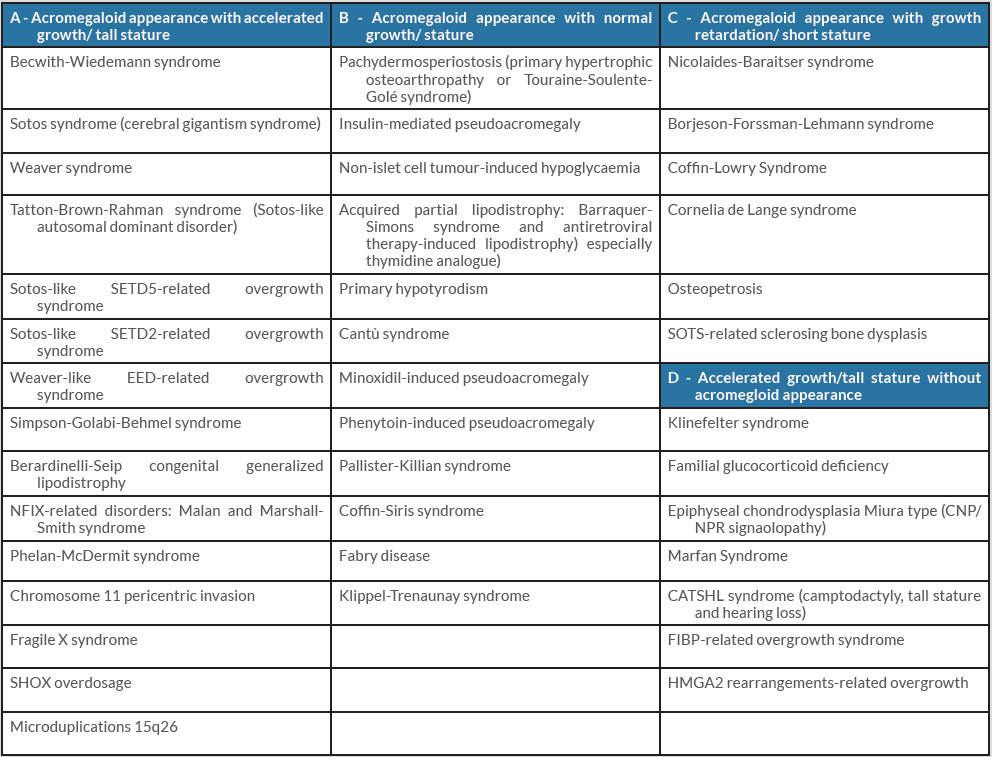

Table 1. The differential diagnosis for pseudoacromegaly. Adapted from Marques and Korbonits[3]

DISCUSSION

Conditions associated with acromegaloidism features have been reviewed thoroughly by Marques and Korbonits (Table 1) [3], and the patient we describe is not similar to those cases reported in the literature. It is well known that growth is mediated by many factors including GH, SM-C, thyroid hormone, sex hormones, insulin and/or PRL and other not yet defined promotors which should be taken into consideration. This is supported by reported accelerated linear growth in some GH-deficient patients [4], and the in vitro stimulation of colony formation of human erythroid progenitor cells in a patient with dwarfism by serum taken from a patient with acromegaloidism where there was no response to GH [5]. Pseudoacromegaly in the presence of pituitary adenoma is one of the difficult clinical scenarios; however, our patient’s features started many years previously when brain MRI was normal and there was normal biochemical testing for acromegaly. This also makes the possibility of burnt-out acromegaly less likely.

In conclusion, clinicians should be aware of the probable aetiologies of pseudoacromegaly and consider biochemical confirmation first in patients presenting with clinical features of acromegaly and pituitary adenoma to avoid unnecessary surgeries.