ABSTRACT

A 39-year-old woman who was taking the contraceptive pill was admitted with right leg deep venous thrombosis (DVT). She was started on apixaban tablets, but after 8 days developed proximal progression of the DVT and pulmonary embolism. Her medical history later showed a history of sleeve gastrectomy. The patient responded to a vitamin K antagonist after heparin. The failure of the antithrombotic drug shed light on the efficacy and changed pharmacodynamics of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) after bariatric surgery in the absence of commercially available blood monitoring tests.

LEARNING POINTS

- Bariatric surgery causes complicated changes in the pharmacodynamics of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

- The absence of clinical data on the efficacy of DOACs after various bariatric procedures makes it difficult to justify their use after bariatric surgery.

KEYWORDS

Apixaban, bariatric surgery, thromboembolism

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 39-year-old woman with a 6-month history of taking an oral contraceptive pill presented with leg pain and mild swelling. There was no chest pain and no haemoptysis. Doppler imaging of the right leg showed a thrombus in the right distal popliteal vein extending to the confluence of the peroneal and posterior tibial veins. ECG and echocardiography results were normal.

The patient was started on 10 mg apixaban twice daily for 1 week, which was decreased to 5 mg twice daily on day 8. This was followed on day 9 by increasing pain and extension of the swelling into the left thigh with difficulty breathing. Physical examination showed the same swelling of the right lower limb, a weight of 104 kg, a BMI of 34 kg/m2, normal vital signs and normal O2 saturation on room-temperature air.

CT angiography showed an acute angled filling defect in the posterior and medial segmental arteries of the lower lobe of the right lung and subsequent subsegmental arteries. An acute angled filling defect was noted in the posterior segmental artery of the upper lobe of the right lung. The right ventricle/left ventricle ratio was 0.85.

Repeated Doppler imaging of the right lower limb showed persistence of the popliteal vein thrombosis with no recanalization. Cranial extension of the popliteal thrombus was noted in the distal superficial femoral vein at the adductor canal. Calf veins (muscular veins) were partially thrombosed in the proximal and mid-calf.

On direct questioning, the patient admitted she had undergone bariatric surgery 4 years before in another facility that was not mentioned in her previous medical records.

All her laboratory tests were normal, including CBC, proBNP and troponin. The results of tests for factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin G20210A mutation, protein S deficiency, protein C deficiency, antithrombin deficiency and antiphospholipid syndrome were all negative.

The patient was started on heparin infusion for 1 week and was maintained on warfarin for 6 months, without any further adverse events or provoked attacks.

DISCUSSION

Bariatric surgery encompasses a variety of procedures, including sleeve gastrectomy (SG), the most common bariatric procedure performed (51.7%); adjustable gastric banding (AGB); Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS)[1]. Bariatric surgeries result in weight loss through (a) restriction of caloric intake by reducing the volume of the stomach (SG and AGB), (b) malabsorption by reducing the effective intestinal surface area (BPD-DS), or (c) a combination of restriction and malabsorption (RYGB and BPD-DS).

Drug absorption will be affected after bariatric surgery as well as bioavailability depending on the chemical properties of the drug (i.e., molecular size and solubility)[2] and on changes in the properties of the gastrointestinal tract (pH, intestinal flow time and surface area available for absorption)[3].

Certain direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) (rivaroxaban) require food to increase absorption and hence bioavailability, which reaches >80% when they are administered with food [4]. Following a restrictive diet after bariatric surgery reduces the absorption of therapeutic rivaroxaban[4]. This effect is not observed with other DOACs or warfarin. Dabigatran requires an acidic environment for absorption[5]. However, after bariatric surgery, the pH in the gastric pouch is more alkaline because of the reduced volume for gastric acid secretion, which could affect dabigatran dissolution and resultant absorption[6].

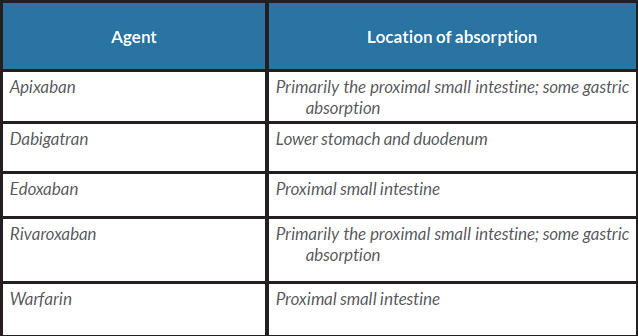

The anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract changes in different ways after different types of bariatric surgery, which may affect the location of drug absorption; in the absence of dedicated studies, indirect evidence can be utilized, such information on the location of drug absorption (Table 1). For example, apixaban is primarily absorbed in the proximal small intestine, with some gastric absorption[7,8]; dabigatran is absorbed in the lower stomach and duodenum[9]; edoxaban is absorbed in the proximal small intestine[10]; and rivaroxaban is primarily absorbed in the proximal small intestine, with some gastric absorption[2].

The use of DOACs in the setting of post-bariatric surgery is not supported by enough literature. One report described the successful use of rivaroxaban following bariatric surgery with a high venous thromboembolism risk, and the anti-Xa levels were monitored[11]. In a total of six patients who underwent SG and six patients who underwent RYGB, the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters were assessed and compared with those in patients before bariatric surgery; the type of surgery did not appear to affect the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of 10 mg prophylactic rivaroxaban once daily, which was well tolerated and considered safe in this trial[12]. For apixaban, there is no approved dosing for obese patients, especially when considering surgical interventions such as bariatric surgery. There is an ongoing study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02406885) to determine the durability or changes in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of apixaban in patients with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or greater following one of two bariatric surgical procedures (preoperative versus postoperative vertical SG or RYGB patients).

Our case report has shown that in the absence of other causes of apixaban failure, a history of SG might cause subtherapeutic levels of the drug, leading to DVT progression and pulmonary embolism. The complicated changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and the absence of clinical data on the efficacy of DOACs after various bariatric procedures as well as the lack of widely available monitoring tests for DOACs, make it difficult to justify their use after bariatric surgery. On the other hand, as the anticoagulant effect of warfarin can be routinely monitored, it is the preferred agent for use in patients after bariatric surgery. If DOACs must be used in patients after bariatric surgery, we suggest checking the drug-specific peak and trough levels. If the drug-specific level is not within the expected range, then a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) should be used.

CONCLUSION

There is little available literature on the effects of bariatric surgery on therapeutic anticoagulation. The changes in drug disposition after bariatric surgery are not predictable without independent studies of individual drugs. At present, it appears most prudent to use a VKA rather than a DOAC for therapeutic oral anticoagulation after bariatric surgery, as VKAs can be easily monitored, and the dose can be easily adjusted.