ABSTRACT

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is the most common antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV). We describe the case of a 38-year-old woman with relapsing GPA who presented with intracranial hypertension, followed by the appearance of cavitated lung nodules despite treatment with azathioprine. Clinical improvement and ANCA titre reduction were observed after rituximab treatment. We report a rare form of GPA relapse and highlight the challenge of following-up patients with GPA, in whom can be hard to distinguish relapse from the consequences of long-term immunosuppression.

LEARNING POINTS

- Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a rare inflammatory disease with pauci-immune focal necrotising lesions that affect small and medium vessels. It has a wide clinical presentation, affecting mainly the upper and lower respiratory tract and kidneys.

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is frequently associated with PR3-ANCA and is risk factor for relapse.

- Follow-up of ANCA titres, which may rise before the development of symptoms, is crucial for recurrence diagnosis. Titres can also be used to distinguish recurrence from the consequences of long-term immunosuppression.

KEYWORDS

ANCA-PR3-associated vasculitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, intracranial hypertension, lung nodules

CASE DESCRIPTION

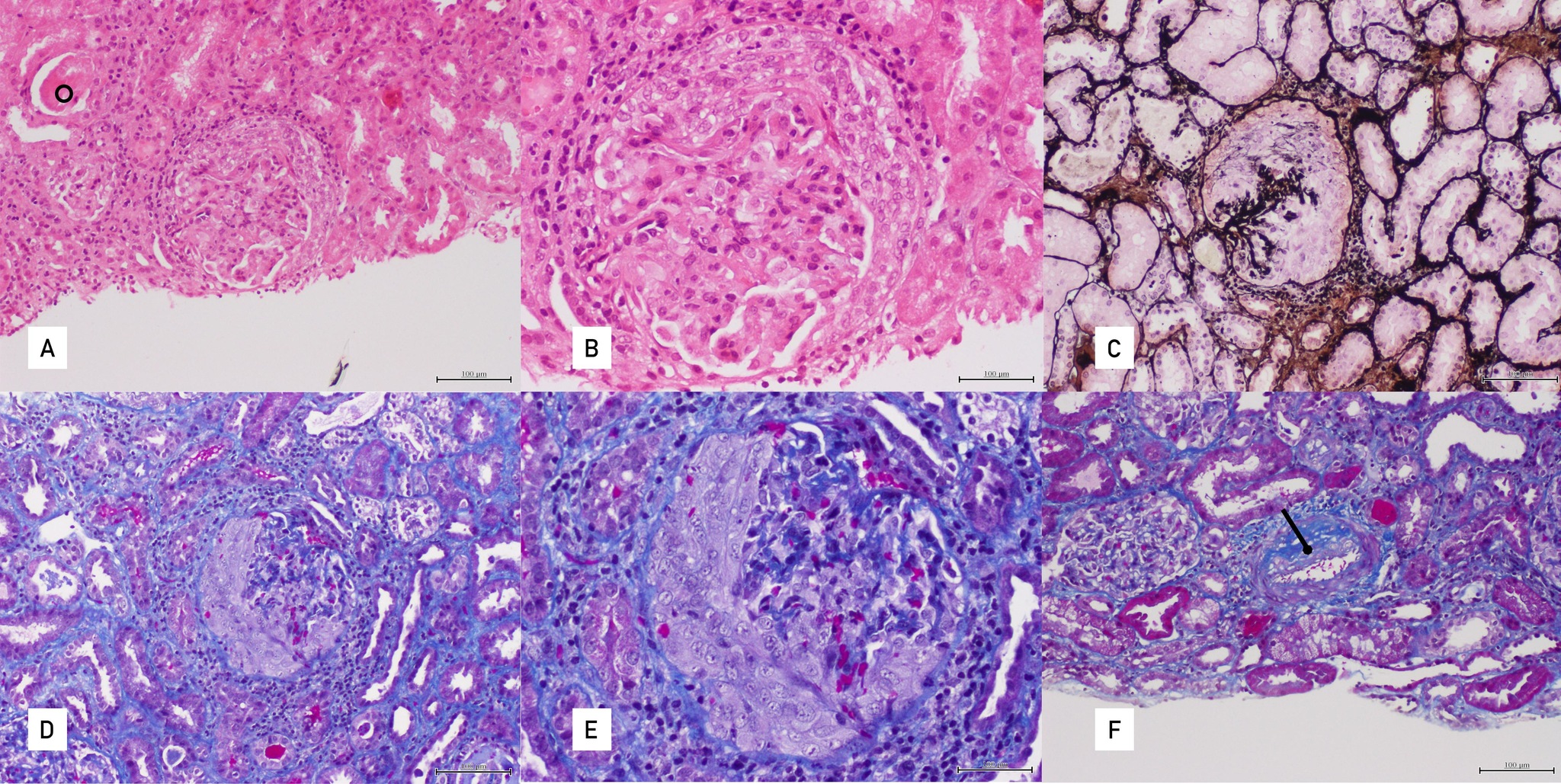

The patient was a 38-year-old woman who had been diagnosed with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) at the age of 29. Her medical history was not relevant. She presented with sinusitis, left uveitis, migratory polyarthralgias, rashes on her palms and soles with target lesions, and fever. Clinical examination revealed positivity for PR3-ANCA, proteinuria with albuminuria (770 mg/gCr), haematuria and renal dysfunction, which improved after the administration of corticosteroids and oral cyclophosphamide. A renal biopsy revealed a pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis (Fig. 1). Maintenance therapy with azathioprine for 20 months was initiated, with decreasing PR3-ANCA titres and improvement of serum creatinine (sCr) values to 1 mg/dl.

Figure 1. Renal biopsy. (A) H&E 100×: Glomeruli with cellular crescents, periglomerular inflammation and tubular casts (circle). (B) H&E 200×: Glomeruli with cellular crescents and periglomerular inflammation. (C) Silver methenamine 100×: Glomeruli with cellular crescents disrupting the silver-positive (stained in black) basement membranes. (D) Masson’s trichrome 100×: Glomeruli with cellular crescents. (E) Masson’s trichrome 200×: Glomeruli with cellular crescents. (F) Masson’s trichrome 100×: Myofibroblastic proliferation within the intimal layer of an artery

Disease relapse occurred 2 years later, with monoarthritis and proteinuria (proteins 0.56 g/l and albumin 120 mg/g), that rapidly improved with oral cyclophosphamide followed by azathioprine and cyclosporine.

After 5 years, the patient was hospitalized due to occipital, pulsatile and refractory headache. Intracranial hypertension was observed with sporadic improvement with acetazolamide.

No further investigation was carried out until PR3-ANCA titres increased (173 UQ) and headache worsened. Cyclosporine was stopped in case it was associated with the neurological presentation. New investigations revealed elevated cerebrospinal fluid pressure (31 cm/H2O) and increased PR3-ANCA (151 UQ), with no other alterations.

Screening for other aetiologies causing the intracranial hypertension was negative and so a relapse of GPA was assumed and induction therapy with rituximab was proposed.

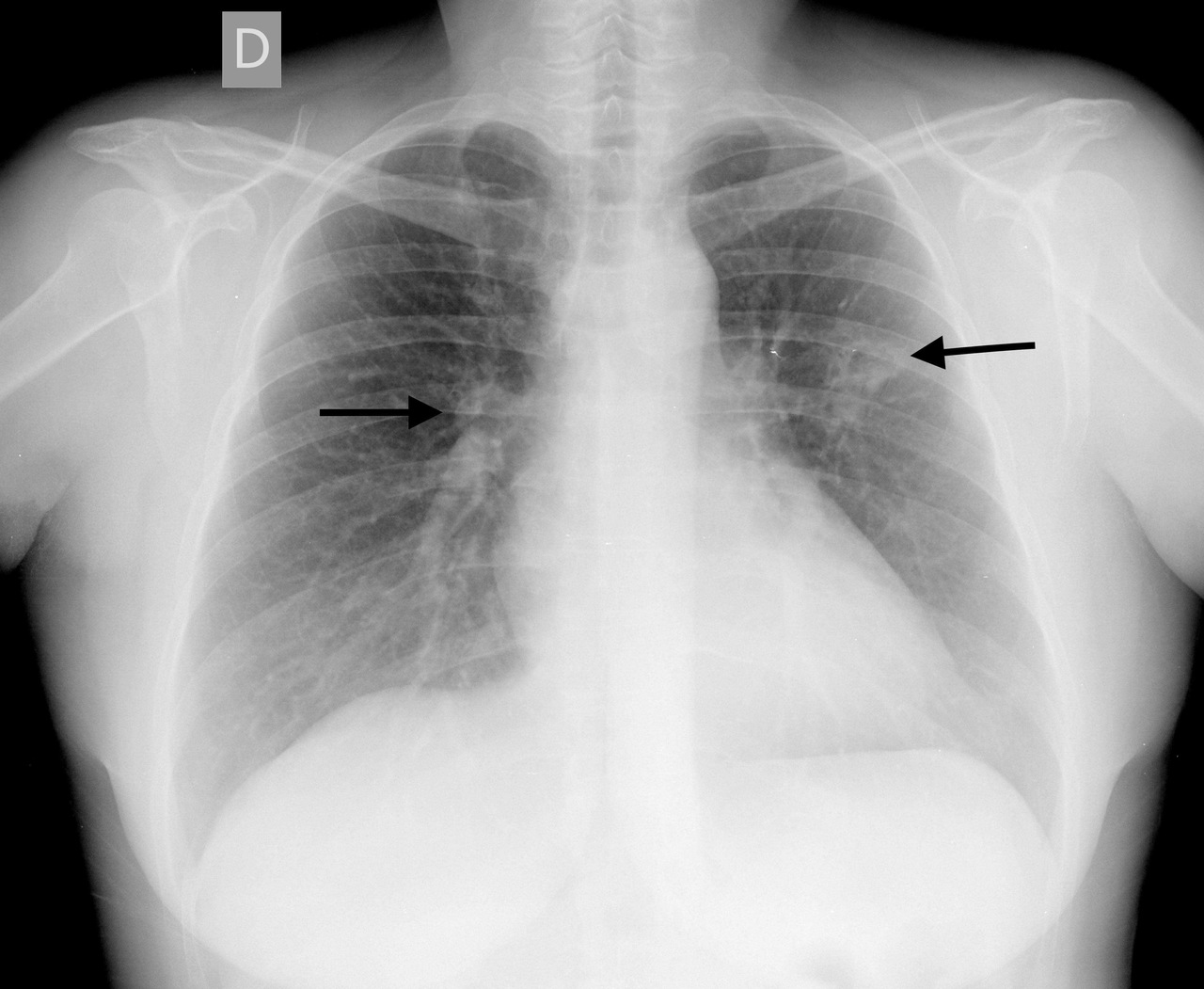

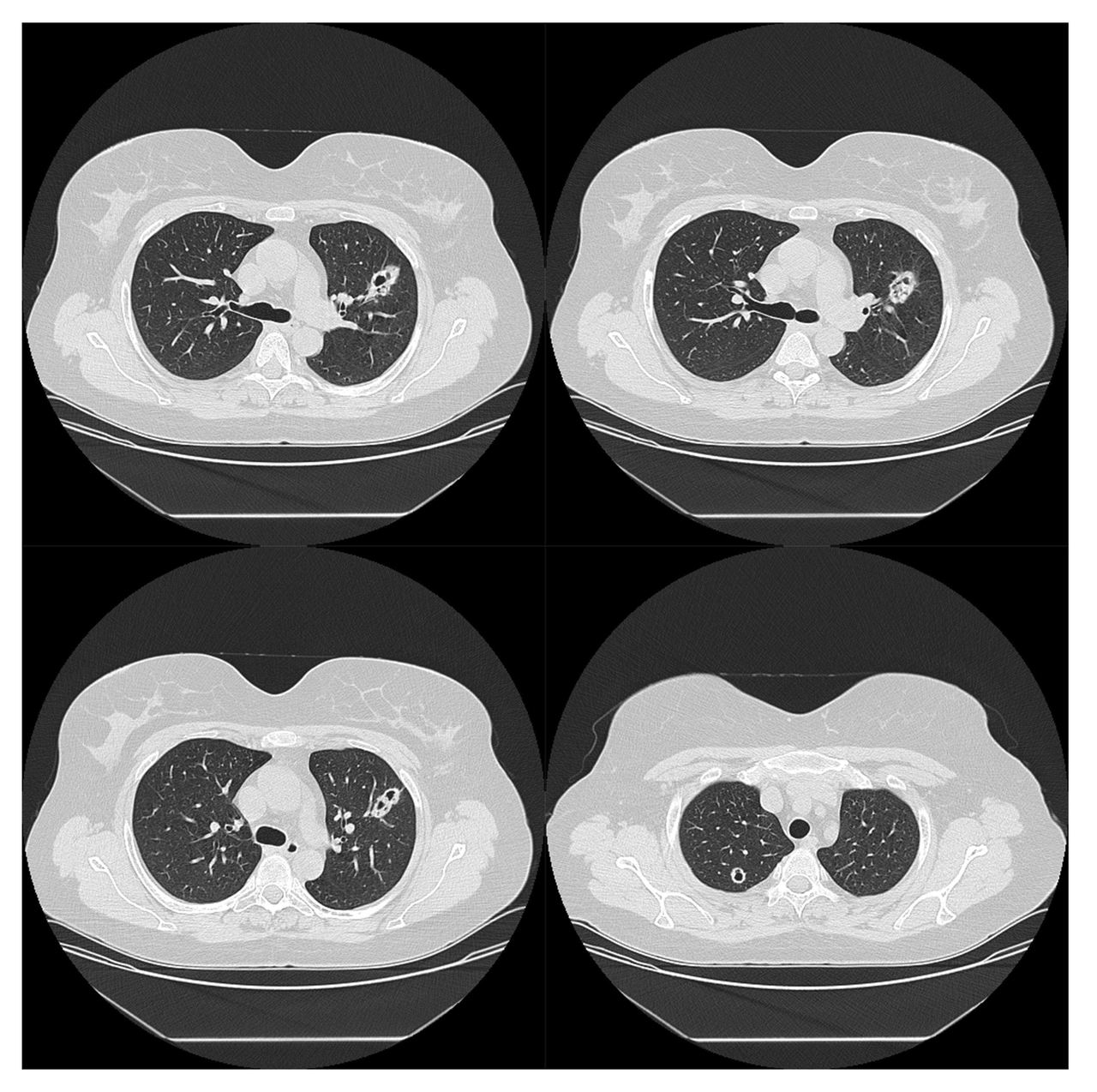

Screening for tuberculosis was performed because of rituximab induction treatment. An interferon gamma release assay and tuberculin skin test were negative and, surprisingly, bilateral cavitated nodular lung lesions were found on x-ray of the thorax (Fig. 2). The lesions were confirmed with a CT scan of the thorax (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Thorax radiograph showing bilateral cavitated nodular lung lesions (arrows)

Figure 3. CT scan of the thorax showing a cavitated nodular formation with a thick wall measuring about 15 mm in the posterior region of the apical segment of the right upper lobe, and an identical oval shape measuring about 29 mm in the anterior segment of the left upper lobe in contact with the left main bronchus and with an intracavitary nodular appearance

Laboratory results showed leukopenia, sCr 1.43 mg/dl, C-reactive protein 10 mg/dl and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 49 mm/hr. Urinalysis revealed protein 20 mg/dl and a protein/creatinine ratio of 0.148 gr/gr.

Analysis of bronchial lavage and aspirate demonstrated 93% macrophages, 6% lymphocytes, 90% CD3, 55% CD4 and <1% CD19. Pathology revealed a filtrate composed of alveolar macrophages. Microbiology and mycobacteriology studies were negative. Immune screening revealed low immunoglobulin A and PR3-ANCA 112.6 UQ.

After exclusion of infectious and neoplastic aetiologies, the diagnosis of GPA relapse was assumed. Rituximab was started with two doses of 1 g separated by 15 days and then with 500 mg every 6 months. Prednisolone dose was reduced until 5 mg per day was reached.

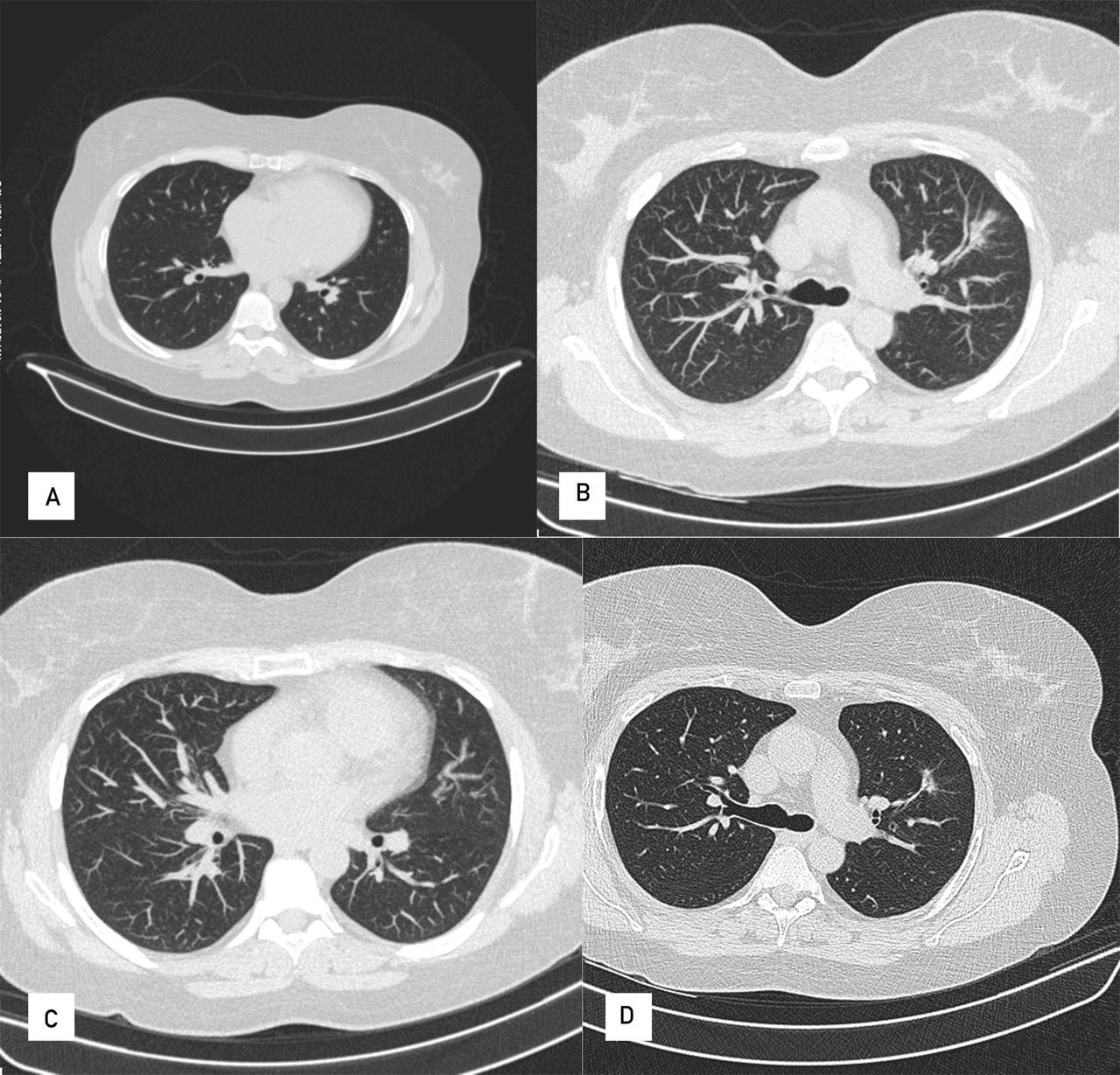

The patient showed suppression of CD19 cells, a reduction in PR3 levels, clinical improvement and improvement on imaging, with residual fibrotic changes in the control CT scan of the thorax (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. CT control scan of the thorax at 6 months with residual fibrotic changes

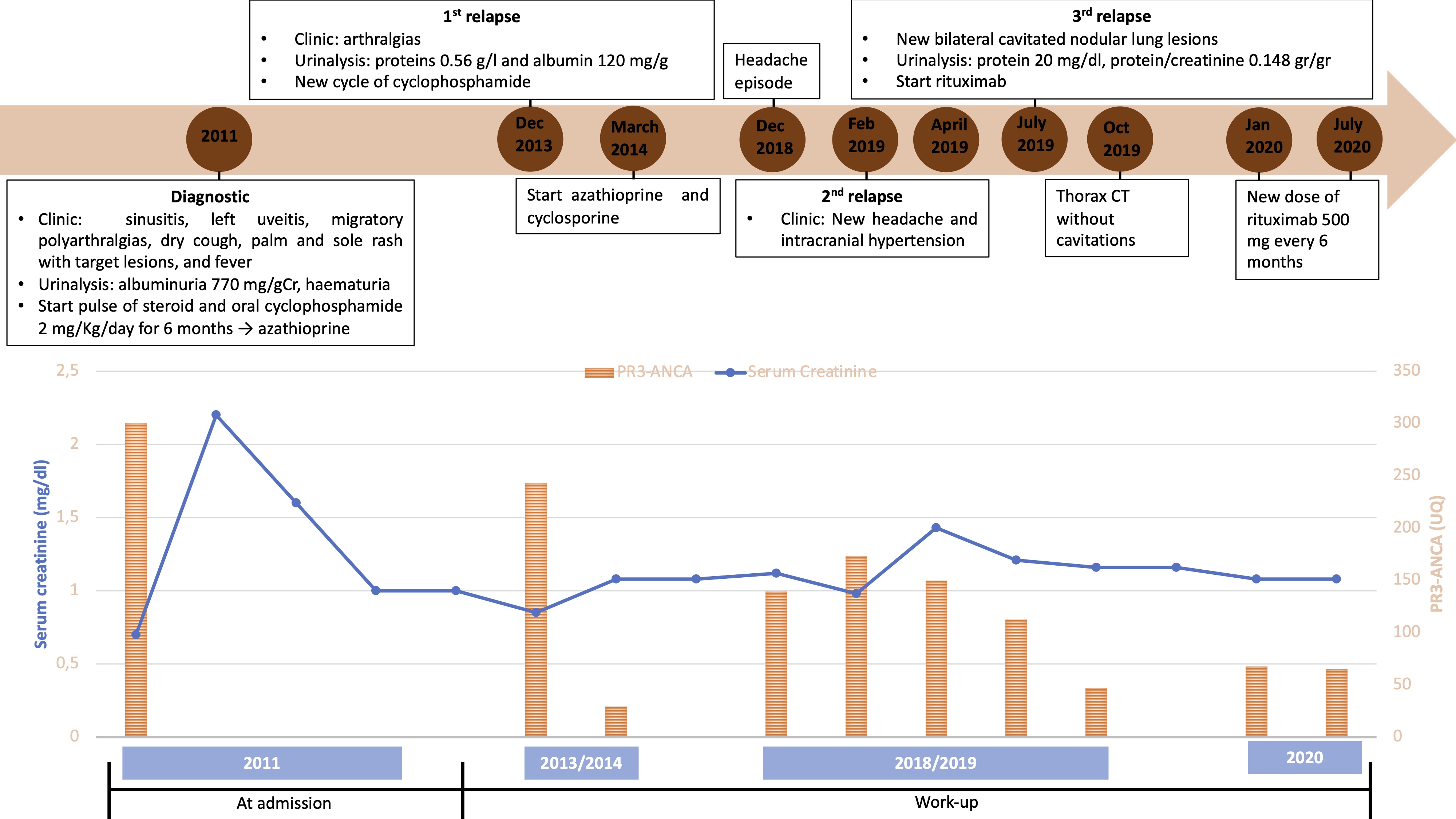

One year after rituximab initiation the patient was asymptomatic, with low, although positive PR3-ANCA of 65 UQ. Figure 5 shows the evolution of sCr and PR3-ANCA titres since diagnosis. CD19 activity remained suppressed.

Figure 5. Graph showing creatinine and PR3-ANCA titre evolution since diagnosis and clinical evolution

DISCUSSION

The main risk factors for GPA recurrence are positivity for PR3-ANCA, plus lung and upper airway involvement. The risk is increased fourfold if all three factors are present. Thus, monitoring of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) titres is crucial during GPA follow-up. In this case, although ANCA titres did not disappear with treatment, they were reduced but did increase with each recurrence. Careful interpretation of clinical data and the results of other investigations is important as proteinuria can occur without kidney dysfunction [1].

In addition to recognising recurrence, it is also important to prevent reoccurrence using the least amount of immunosuppressive therapy. For decades, conventional treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) with major organ involvement has been the administration of cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoids, and then azathioprine. Recently, rituximab has also been used, and has a particular role in treating relapses and GPA [2, 3].

Although headache is a common symptom, isolated intracranial hypertension is a rare manifestation of GPA [4]. On the other hand, pulmonary involvement ranges from subclinical changes to serious haemoptysis. The most common abnormalities seen on imaging are lung nodules, frequently with cavitation suggesting active disease, air-space and ground-glass opacities. Most cavities are thick walled and tend to have irregular inner margins, but they may become thin walled and decrease in size, or even disappear with treatment. However, a cavitated lung lesion is an unspecific finding and other diseases including neoplasm, infection, pulmonary infarct and septic embolism need to be excluded[5].

In conclusion, AAV can have diverse clinical presentations and recurrence is frequent. Consequently, close clinical and analytical follow-up, especially with ANCA titres, is important to correctly balance sufficient immunosuppression to treat and prevent occurrence, with the lowest possible dose to avoid short- and long-term consequences.