ABSTRACT

Hepatic adenomatosis (HA) is a very rare condition and defined as the presence of 10 or more adenomas in an otherwise normal liver. HA has an incidence of 10–24% in patient with hepatic adenoma and it is more common in women. Most patients with HA are asymptomatic with a normal liver function test and half of cases are detected incidentally on imaging. Although HA is considered a benign disease, some patients may develop potentially fatal complications, such as hypovolaemic shock due to rupture of the liver lesion or malignant transformation to hepatocellular carcinoma.

We report the case of a 29-year-old woman who presented to the emergency room after a car accident. Whole-body computed tomography revealed multiple focal hepatic hypervascular lesions in the right lobe of the liver together with a fatty liver. Subsequent hepatic magnetic resonance imaging suggested the diagnosis of HA with a suspicion of focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). The patient refused to undergo liver biopsy, so we instituted a 3-month surveillance program, which included clinical assessment, liver function tests, tumour marker assessment and blood tests as well as sonographic evaluation for follow-up of the liver lesions.

LEARNING POINTS

- Hepatic adenomatosis is an extremely rare disease which predominantly affects women and is associated with hormone consumption, liver steatosis, glycogen storage disease, obesity, metabolic syndrome, abnormalities of hepatic vasculature and maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY).

- The two main differential diagnoses include focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) and well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Histological confirmation is required when MRI findings are inconclusive or when a malignancy is suspected.

- In men, resection of adenomas is mandatory due to the high risk of malignant transformation. In woman, a conservative approach with contraceptive discontinuation and biannual follow-up with MRI and alpha-fetoprotein is recommended; resection is needed in case of positive immunohistochemical staining for β-catenin on biopsy, symptomatic adenomas, adenoma increasing in size, and when malignancy cannot be ruled out.

KEYWORDS

Hepatic adenomatosis, hepatic adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia, steatosis hepatis

CASE DESCRIPTION

We describe the case of a 29-year-old Caucasian woman who was referred to our outpatient clinic for further investigation after a diagnosis of multiple focal hepatic hypervascular lesions in the right lobe. In May 2021 the patient had been in a car accident and underwent total-whole computed tomography (WBCT) which revealed multiple focal hepatic hypervascular lesions in the right lobe of the liver together with a fatty liver.

Two months later in August 2021, she presented in our outpatient clinic. Her past medical history was unremarkable. She had no smoking history and had been taking oral contraceptives for the previous 14 years. Apart from this, there was no other relevant personal or family history. She denied taking any over-the-counter medication or using recreational drugs. She was asymptomatic and her physical examination, including blood pressure and temperature, was unremarkable. Her body mass index (BMI) was 27. Laboratory analysis revealed increased alanine transaminase of 38 U/l and gamma-glutamyl transferase of 44 U/l. Cholesterol at 5.7 mmol/l and LDL cholesterol at 3.9 mmol/l were above the upper limits. Serum ferritin levels were elevated at 146 µg/l, while serum iron levels and transferrin were normal. Her blood count, coagulation tests, renal function, and sodium and potassium were normal, as were levels of bilirubin, albumin, glycated haemoglobin and alpha-fetoprotein.

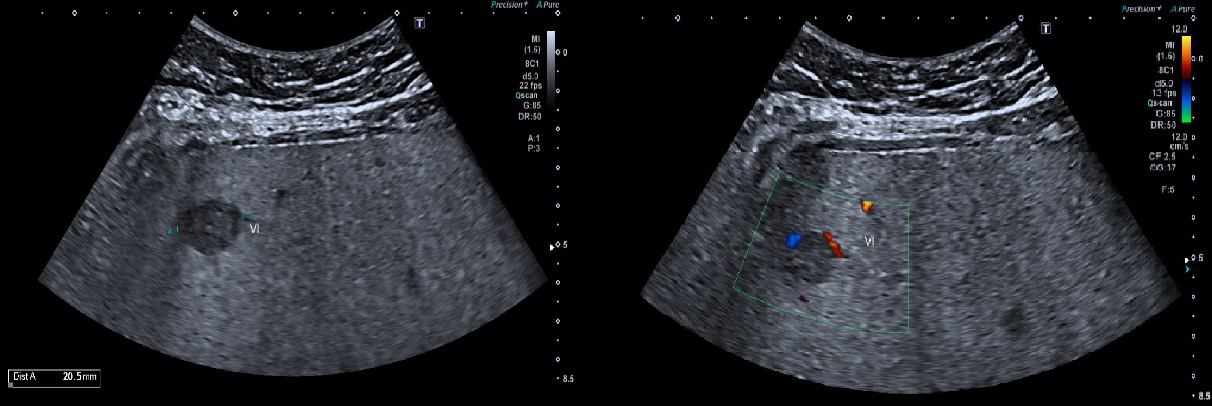

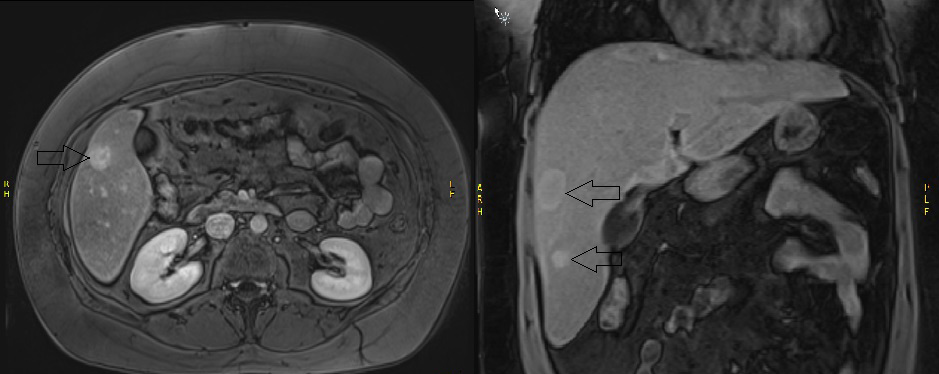

An abdominal ultrasound was performed and showed hepatomegaly with steatosis and several hypoechoic lesions in the right lobe of the liver. The largest lesions were in segments 5 and 6, that in the latter measuring >20.5 mm and showing peritumoral vessels on Doppler examination (Fig. 1). A FibroScan showed no fibrosis, but a high controlled attenuation parameter of 375 dB/m was suggestive of severe steatosis. Subsequent hepatic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 2) showed liver steatosis with hepatomegaly and 10 liver lesions in the right lobe.

Figure 2. Liver MRI showing multiple liver lesions in an otherwise normal liver

They were slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted images, with hypervascular enhancement on the arterial phase, remaining hyperintense on the portal venous phase and hypointense on the hepatobiliary phase apart from the lesion in segment 6, which was characterized by a garland-like enhancement during the hepatobiliary phase, suspicious for focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). The largest lesion was found in segment 5 and measured 23×22 mm. The case was presented and discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting in a tertiary referral hospital. The patient refused liver biopsy so histological confirmation of the liver lesions, especially the lesion in segment 6, could not be performed. Based on clinical, laboratory and radiological findings, we made the pragmatic diagnosis of multifocal hepatic adenomatosis with associated non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. A conservative approach was adopted with 3-month imaging and laboratory follow-up. The patient stopped using oral contraceptives and modified her lifestyle.

DISCUSSION

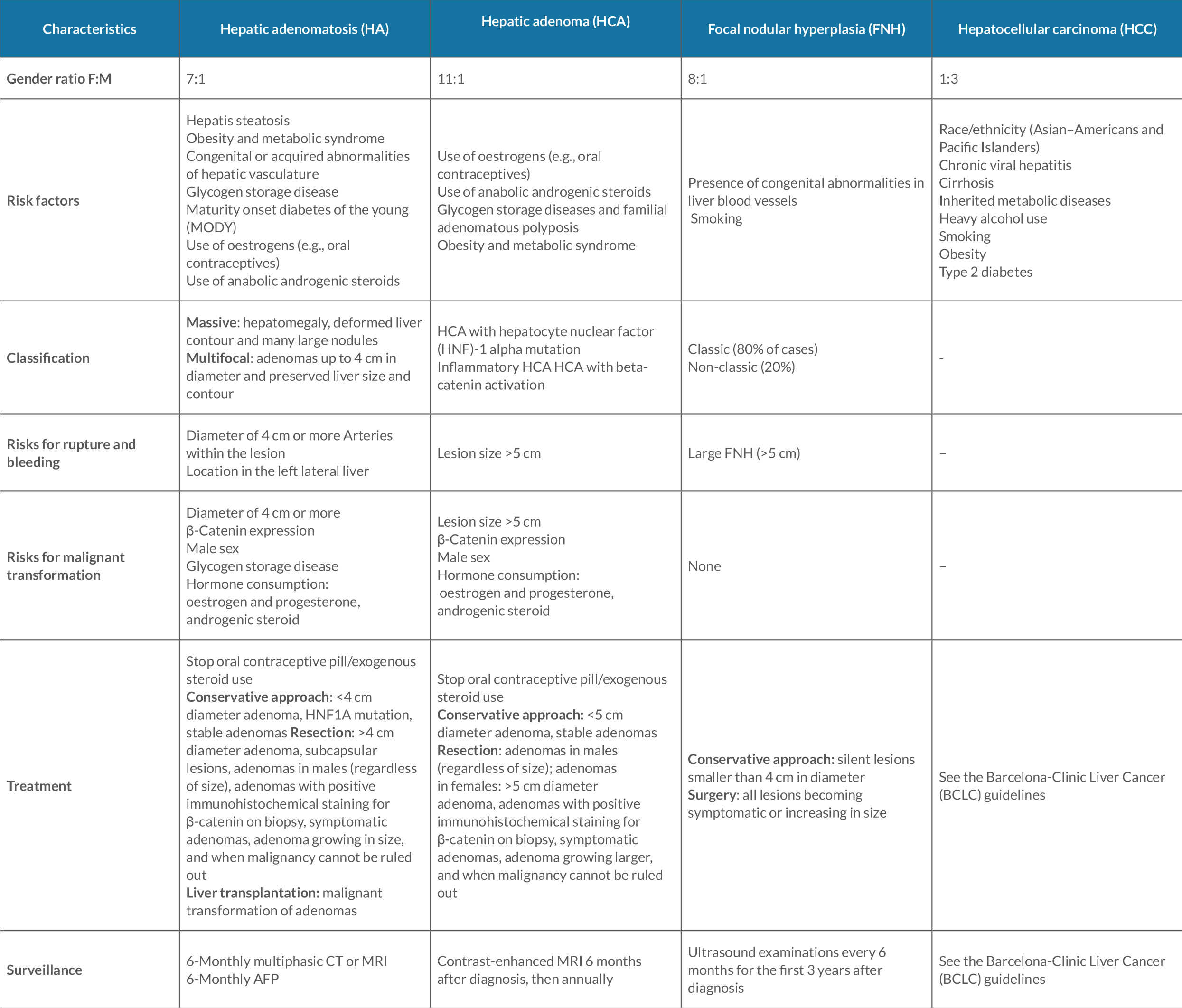

Hepatic adenomatosis (HA) is defined as the presence of 10 or more adenomas in an otherwise normal liver and was first described by Flejou et al. [1]. HA is a very rare condition and less than 100 cases have been reported in the literature. HA affects women more than men (female:male ratio of 7:1), as does liver adenoma (female:male ratio of 11:1) [2]. In HA, the association with oral contraceptive use is not as high as in solitary liver cell adenomas [2]. The diagnosis of HA is the same as that for hepatic adenoma and is based on contrast-enhanced, cross-sectional imaging using multiphase MRI [3]. Histological confirmation is not required for a woman unless MRI findings cannot clearly differentiate liver cell adenoma from focal nodular hyperplasia or hepatocellular carcinoma [2]. For male patients, the diagnosis is generally confirmed with histology obtained at the time of surgical resection [2, 4]. The aetiology is unknown, although HA has been associated with the use of oral contraceptives, anabolic steroids, some storage diseases, hepatis steatosis, obesity and metabolic syndrome [5]. HA exists in two forms as suggested by Chiche et al [3]: massive and multifocal. Patients with the multifocal type are unlikely to develop symptoms and appear to have a less aggressive clinical course [3]. The liver function abnormalities are usually related to the space-occupying nature of tumours. Increases in serum alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase are common in HA but uncommon in liver adenoma [1–3, 5]. The progression of untreated HA is not well understood and consensus is lacking regarding management. To the best of our knowledge, as reported by Barthelmes et al. [2], approximately 81 cases of HA have been documented in the literature with an average documented follow-up period of 57 months (range 3–180 months). These data showed that 41 patients have stable disease, 34 have disease with increased size and/or number of lesions, and 6 (7%) have developed malignancy. The risk of malignant transformation is not increased compared with solitary liver cell adenomas, but as these patients have multiple lesions, the risk of bleeding is substantially higher (46% in patients with HA versus 20–30% in patients with hepatic adenomas) [2]. Treatment consists of resection of adenomas in males regardless of size [1, 2]. For woman, resection is needed in case of large lesions >4 cm in diameter, sub-capsular lesions, adenomas with positive immunohistochemical staining for β-catenin on biopsy, and symptomatic adenomas [2]. Liver transplantation is the last resort if there is substantive concern about malignant transformation or for large, painful adenomas in liver cell adenomatosis after treatment attempts by liver resection [2]. Table 1 shows the characteristics of HA, hepatic adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. There is no consensus about surveillance, but biannual follow-up with CT or MRI and alpha-fetoprotein measurement is generally accepted [2, 3, 5]. All female patients should be advised to stop hormone treatment (e.g., oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy) [2]. HA in pregnant women requires special consideration because of the risk of hormone-induced growth and spontaneous rupture, which may threaten the life of both mother and child [2]. Although most cases are asymptomatic at diagnosis, it is essential to carry out an extensive investigation to identify the severity of disease. Moreover, we underline the importance of stratifying high-risk patients in whom a definitive histological diagnosis may not be possible and initiating personalized follow-up.