ABSTRACT

Biliary hamartomas or von Meyenburg complexes (VMCs) are hepatic tumour-like lesions related to congenital malformation of the ductal plate, and are part of the ciliopathy spectrum of disorders. The exact pathogenesis of VMCs is unclear and it remains controversial whether they have the potential for malignant transformation. Patients are often asymptomatic and VMCs are usually encountered as an incidental finding on imaging. We report a case of recurrent sepsis with an unidentified focus. It was later confirmed that biliary hamartomas were acting as a sanctuary for the persistent pathogenic agent. The authors hope to draw attention to the existence of this unusual focus of recurrent sepsis.

LEARNING POINTS

- Hepatobiliary sepsis is an unusual clinical presentation of biliary hamartomas.

- Clinicians should be aware of the infectious complications of these diffuse structural biliary ductal abnormalities.

- Early recognition of this atypical life-threatening clinical presentation is important for the prognosis.

KEYWORDS

Biliary hamartoma, von Meyenburg complex, sepsis, hepatic lesions

CASE DESCRIPTION

The patient was a 69-year-old man with a history of ischaemic heart disease, chronic liver disease, adrenal incidentaloma, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, hyperuricaemia and dyslipidaemia. He had a recent medical history of four hospital admissions in the previous 5 months due to bacteraemia caused by extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, with an unknown focus of infection.

The patient presented to the emergency room with fever, dyspnoea and dizziness. Physical examination revealed diffuse abdominal pain, without Murphy’s sign. Blood work revealed elevated plasma C-reactive protein and plasma procalcitonin, which was more than two standard deviations above the normal value. Blood culture was negative. Abdominal ultrasound showed a heterogeneous liver and cholelithiasis.

In view of the findings, the hypothesis of a focus of infection in the gallbladder and biliary tract was considered and the patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy, during which several hepatic lesions were identified and biopsied. Histology of these lesions revealed calcified biliary hamartomas, while bacteriology confirmed the presence of K. pneumoniae in the sample. After recovery, the patient was discharged with clinical improvement.

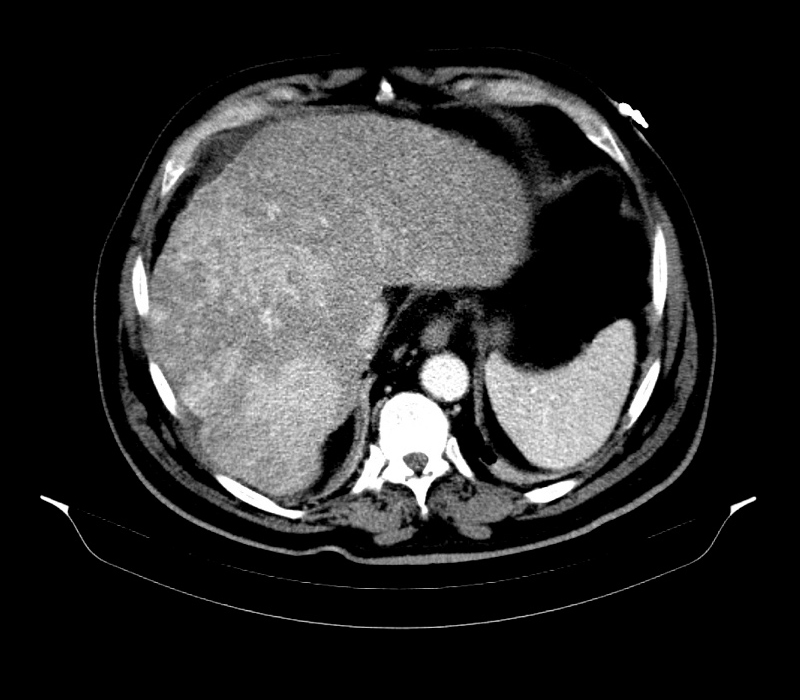

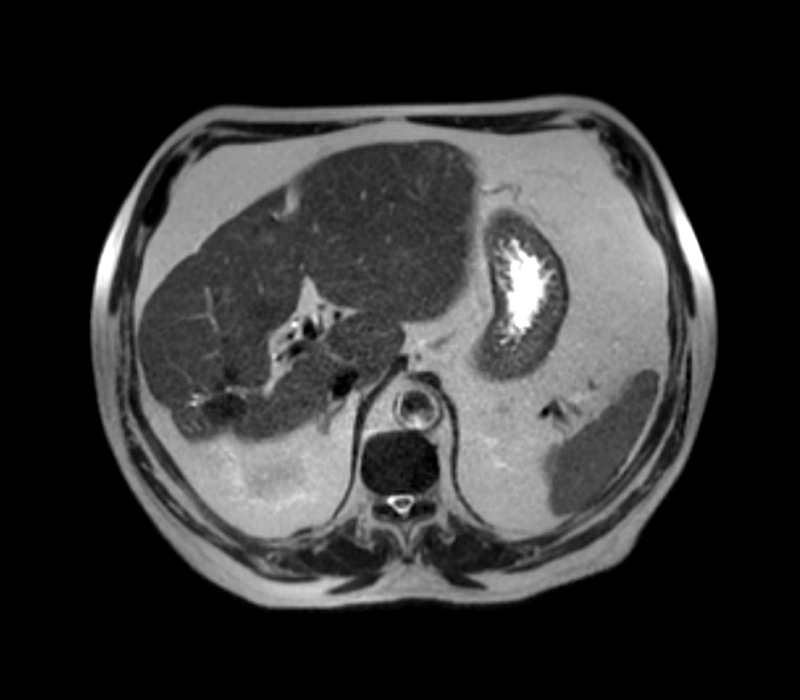

One month after surgery, the patient was re-admitted to the intensive care unit with bacteraemia due to ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae. The abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a liver with increased dimensions, a heterogeneous texture due to the presence of multiple calcified lesions, related to granulomas, and a hypodense area (24 mm) in the left lobe (segment III) in a subcapsular location (Fig. 1). The subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several nodular lesions, probable calcifications, the largest measuring 2.8 cm, and morphological alteration of the liver with evident hypertrophy and chronic hepatopathy (Fig. 2). The hepatobiliary scintigraphy showed normal appearance of the bile ducts, with no obstruction. Considering the multiple admissions due to recurrent sepsis, the case was discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting in a tertiary hospital. At this meeting, the hypothesis of a liver transplant was ruled out due to the MRI showing benign lesions and the absence of signs of hepatic cirrhosis.

Figure 1. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan performed at admission showing the liver with increased dimensions and a heterogeneous texture caused by the presence of multiple calcified lesions, suggestive of granulomas

Figure 2. Abdominal MRI performed at admission showing several nodular lesions and morphological alteration of the liver with evident hypertrophy and chronic hepatopathy

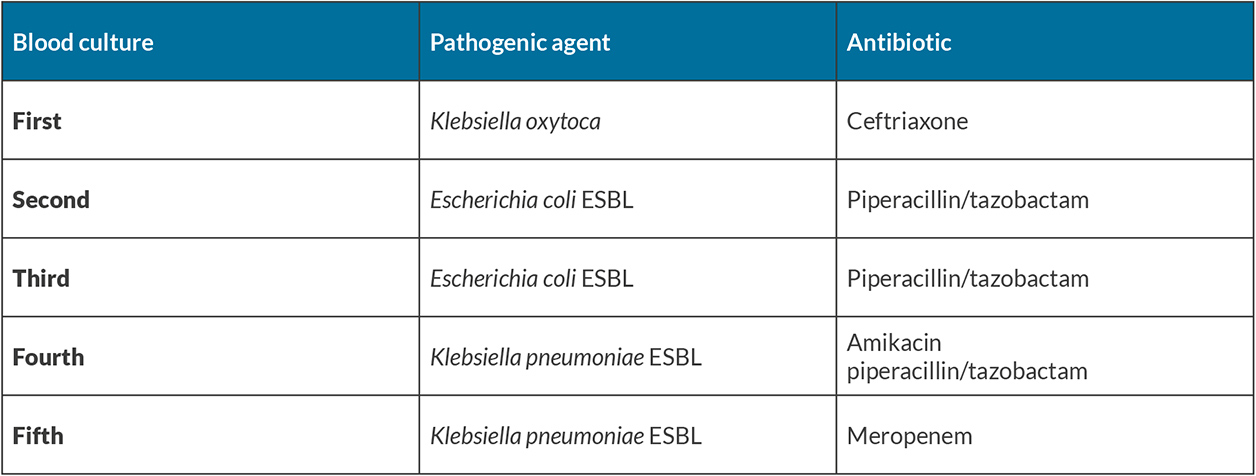

Because of the recurrent sepsis, the patient underwent multiple sequential cycles of different broad-spectrum antibiotics, adjusted according to antibiotic sensitivity tests. In brief, the patient was treated with meropenem 1 g, three times a day for 14 days, amikacin 500 mg, twice a day for 17 days, piperacillin and tazobactam 4.5 g, four times a day for 17 days, and ceftriaxone 1 g, once a day four 10 days (Table 1). The patient had a favourable clinical evolution and improvement after each cycle of antibiotic therapy, and was discharged at the completion of treatment.

Four months after surgery, the patient was readmitted again with sepsis and bacteriaemia due to ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae. The focus of infection was hypothesized to be the biliary hamartomas, which acted as reservoir for the persistently identified pathogenic agent. To sterilize the cystic content and resolve the recurrent sepsis, the patient underwent an extended cycle of antibiotic therapy with meropenem 1 g, three times a day for 21 days. After 3 weeks, the patient was discharged with prophylactic antibiotics and remained under surveillance by a consultant.

After 3 years of follow-up, the patient has not relapsed or experienced any other symptoms related to the previous admissions. Currently, the patient is on a prophylactic antibiotic with ciprofloxacin 500 mg, twice a day, and annual MRI to evaluate the stability of the hepatic lesions.

DISCUSSION

Biliary hamartomas or von Meyenburg complexes (VMCs) are hepatic tumour-like lesions, first described by von Meyenburg in 1918[1]. They are benign cystic lesions of the liver that consist of focal collections of duct-like structures embedded in a fibrous stroma resulting from ductal plate malformation involving the small interlobar bile ducts[2]. VMCs are a rare incidental finding and, based on autopsy studies, their prevalence is approximately 5.6% in adults and 0.9% in children. Histologically, they consist of disorganized and dilated bile ducts surrounded by fibrous stroma[3]. They are usually scattered throughout both liver lobes, especially in the subcapsular region of the liver[4].

With the improving imaging modalities, these lesions have been more frequently identified radiographically, and they present a distinctive appearance on imaging[5]. Ultrasound findings have been described as demonstrating multiple micro-nodules that may show comet-tail artifacts, which explains why they are difficult to differentiate from aerobilia and from intrahepatic stones[4]. On contrast enhanced CT, biliary hamartomas are low-attenuation lesions and may have irregular margins, suggestive of liver metastases[6]. On MRI, VMCs appear as non-enhancing lesions, which are hypointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging[7]. In this present case, multiple calcified lesions were identified which were not suggestive of liver metastases and did not have comet-tail artifacts on ultrasound.

VMCs are rarely diagnosed clinically since most patients are asymptomatic, and they are an incidental finding on imaging. Nevertheless, VMC case reports have described different clinical manifestations, including jaundice and portal hypertension as a result of mass effect[2,3,5,6,8–13]. In a review of the literature, the authors found one case of a VMC patient presenting with recurrent life-threatening hepatobiliary sepsis which was refractory to medical therapy[1].

The presumptive pathogenesis for the recurring sepsis in our patient is likely biliary stasis, leading to superinfection of the cystic contents which makes sterilization hard to achieve. Another potential explanation could be excess mucous secretion resulting in biliary obstruction and ascending infection.

In this clinical case, treatment with antibiotics should have resolved the hepatobiliary sepsis. However, sepsis recurred despite the adequate antibiotic treatment of each episode of sepsis; the exact trigger has not been established. The prophylactic administration of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin resulted in clinical stability and prevented further admissions with a similar clinical presentation.

Although VMCs are a benign condition, some reports have showed malignant transformation to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma[9]. Some authors suggest periodic clinical and imaging monitoring and the determination of cancer antigen 19-9. If the patient develops resistant organisms and becomes refractory to treatment, liver transplantation could be an alternative for the management of recurrent sepsis from VMCs[5]. Recurrent biliary sepsis is an accepted indication for liver transplantation as in primary sclerosing cholangitis and Caroli disease.

CONCLUSION

Hepatobiliary sepsis is an unusual clinical presentation of the rarely diagnosed VMCs. Clinicians should be aware of the infectious complications of these diffuse structural biliary ductal abnormalities. The authors highlight the importance their recognition as patients may present with atypical life-threatening infection.