ABSTRACT

A 21-year-old male patient with a history of occupational exposure to open fire smoke was initially treated with empiric antibiotics for simple community-acquired pneumonia. However, he continued to deteriorate rapidly, developed respiratory failure and needed mechanical ventilation. After possible aetiologies were considered, acute eosinophilic pneumonia was suspected and confirmed by broncho-alveolar lavage. His condition improved dramatically soon after glucocorticoid administration and he was discharged without sequelae. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia should be considered in a patient with a history of exposure to smoke presenting with pneumonia that deteriorates rapidly despite broad antibiotics. An important clue for the diagnosis is eosinophilia in peripheral blood.

LEARNING POINTS

- Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) should be considered in any patient with pneumonia and peripheral blood eosinophilia.

- A detailed medical history, including exposure to cigarette or occupational smoke, is critical in all patients with pneumonia, especially in non-resolving cases.

- Once AEP is diagnosed, prompt glucocorticoid treatment usually leads to an immediate and dramatic response.

KEYWORDS

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia, occupational exposure, eosinophilia

INTRODUCTION

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP) is an uncommon syndrome which affects mostly young, otherwise healthy patients, with cigarette smoking being a major risk factor. The clinical presentation can be misleading as patients present with non-specific respiratory symptoms which are similar to those of the far more common bacterial pneumonia. Rapid diagnosis is crucial as the clinical course is progressive and treatment highly effective, usually leading to complete recovery. We present an unusual case of eosinophilic pneumonia in a non-smoker with occupational smoke exposure treated in our ward.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy, 20-year-old male arrived at the emergency department after 2 weeks of fever of up to 39.5°C, productive cough, night sweats, malaise and myalgia. He reported being a non-smoker. His medical history was unremarkable except for occupational smoke exposure. He had been serving as a policeman in a region of rural villages where domestic waste is traditionally burnt on open fires, thus creating severe air pollution. He had been treated with roxithromycin for 7 days prior to admission with no clinical response.

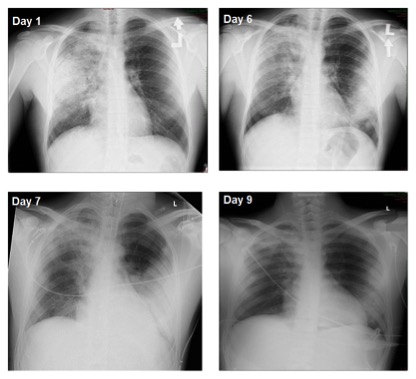

His temperature at arrival was 38.4°C, blood pressure 130/70 mmHg, pulse 88 bpm and oxygen saturation 97% in room air. Physical examination disclosed dyspnoea and tachypnoea. Auscultation of the lungs revealed bronchial breathing sounds, with crackles noted over the right lung. Laboratory work-up showed white blood cells 11.54×103/µl, total eosinophils 92×104/µl, haemoglobin 13.7 g/dl, creatinine 1.1 mg/dl and C-reactive protein (CRP) 11 mg/dl. Liver enzymes were elevated: ALP 524, GGT 320, ALT 406 and AST 137. Abdominal ultrasound was normal. A chest radiograph demonstrated infiltrates involving most of the right lung (Fig. 1A).

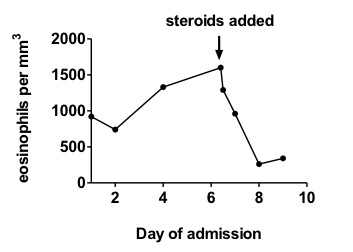

Treatment with intravenous (IV) cefuroxime was initiated following admission. Blood and sputum cultures as well as a urine Legionella antigen test were all negative. Following 48 h of persistent high-grade fever (up to 40°C), the antibiotic treatment was changed to moxifloxacin. Blood cultures were still sterile at this point. During the next 48 h the patient showed respiratory distress with persistent fever. Oxygen saturation dropped to 88% suggesting evolving respiratory failure. Arterial blood gas disclosed PaO2 67 mmHg and CRP increased to 14 mg/dl along with elevated liver enzymes. A complete blood count revealed leucocytosis 12.8×103/µl and eosinophil count 1.33×103 cells/µl.

A follow-up chest radiogram (Fig. 1B) demonstrated progression of the pulmonary findings to diffuse bilateral infiltrates, suggesting AEP. The following day, respiratory distress worsened and the patient was intubated, mechanically ventilated, and transferred to the intensive care unit.

On day 6, broncho-alveolar lavage demonstrated 30% eosinophils, leading to the diagnosis of AEP. IV glucocorticoids were administered with prompt improvement. Recovery occurred within hours, including resolution of fever and successful extubation within 24 h. A chest radiogram revealed considerable regression of the bilateral infiltrates (Fig. 1D). The eosinophil count dropped to 260 cells/µl (Fig. 2).

The patient was discharged 2 days later on oral prednisone, 60 mg/day with tapering over 3 months.

Figure 1. Posterior-anterior chest radiographs of the patient taken on different days of hospitalization, as indicated.

Steroid treatment was initiated on day 6. Note the diffuse bilateral massive infiltrates on days 1–7 that are characteristic of acute eosinophilic pneumonia, and considerable resolution on day 9

Figure 2. Total blood eosinophil count during hospitalization.

Note mild eosinophilia during presentation with progressive increases as the patient's condition deteriorated, and the rapid decrease in eosinophil count after glucocorticoid administration (day 6)

DISCUSSION

AEP is a relatively new and uncommon syndrome first described in 1989 but with few reported cases[1]. Patients may rapidly develop respiratory failure and require mechanical ventilation. AEP usually affects young, healthy patients. The male/female ratio is 1.5:1 and the mean age at presentation is 29 years[2]. The aetiology of AEP has still to be elucidated. However, it is associated with various exposures including cigarette smoke (active and passive), noxious chemical exposure, dust and medications.

Tobacco smoke is the most frequent exposure factor[3,4], with even short-term exposure to passive smoking or smoke leading to AEP[5]. In a cohort of young military personnel deployed in Iraq, recent onset (median 1 month) of smoking was reported in 78% of patients diagnosed with AEP and an incidence of 9.1 per 100,000 person-years[6]. High prevalence and recent onset of smoking are associated with developing AEP, as reported in another recent study of a cohort of 137 cases of AEP among whom 99% were smokers and more than 50% had started to smoke less than a month before developing the condition[7]. Although the leading known exposure factor is cigarette smoke, anecdotal cases have described AEP after occupational exposure[8]. Our case is unique because the reported exposure factor was fire smoke rather than cigarettes.

Clinically, AEP presents with fever and non-specific respiratory symptoms including dyspnoea, tachypnoea and cough and is difficult to differentiate from the far more common bacterial pneumonia at presentation, so diagnosis is often delayed. An important clue can be peripheral blood eosinophilia revealed by laboratory studies, but a normal eosinophilic count at presentation is quite common and does not exclude the diagnosis[7]. Eosinophilia becomes markedly elevated as AEP evolves[8]. The natural history of AEP is rapidly progressive and some patients proceed from symptom onset to mechanical ventilation in less than 24 h.

Chest radiographs may show diffuse bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and chest CT scans may show consolidations, ground-glass opacities, pleural effusions and interlobular septal thickening. Bilateral areas with ground-glass attenuation (100%), interlobular septal thickening (90%) and pleural effusions (79%) are the most common CT findings[9].

Because the presentation of AEP may be indistinguishable from other more common diseases, broncho-alveolar lavage is crucial in establishing the diagnosis. Finding more than 25% eosinophils in the white cell count is characteristic of AEP. Lung biopsy is not usually required for diagnosis.

AEP should be considered in cases of rapidly progressing respiratory failure. Most patients with AEP are severely hypoxaemic, require mechanical ventilation, and meet the criteria for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

The treatment for AEP is prompt administration of IV corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 240–1,000 mg/day IV in divided doses). The response is often dramatic with some patients being removed from mechanical ventilation within 24 h of steroid administration.

Once respiratory symptoms resolve, treatment can be switched to oral glucocorticoids (prednisone 40–60 mg/day) and tapered over 3 months. Resolution without recurrence or long-term pulmonary complications is reported in most cases[10].

CONCLUSION

AEP is a rare disease requiring a high index of suspicion for accurate and timely diagnosis. Clues that can help the primary physician include failure to improve from what initially seems to be straightforward infectious pneumonia and continuous deterioration even after second-line broad antibiotics. This report highlights the importance of a detailed medical history taking into account other potential exposures, such as fire smoke. The second clue is peripheral blood eosinophilia, which is usually not encountered in the setting of sepsis[11-13].