ABSTRACT

Objective: Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a group of pathologies of undetermined frequency that require a broad differentialdiagnosis and continue to pose a challenge for clinicians.

Observations: We present a clinical case of a 17-year-old male with acute interstitial pneumonitis, lung aspergillosis and foreign body lung granulomatosis after carbon monoxide (CO) intoxication. As far as we know, no similar cases have beenreported in the literature.

Conclusions: ILD require a broad differential diagnosis, which is of great importance to prognosis.

LEARNING POINTS

- The diagnostic work-up and treatment of interstitial lung diseases should be guided by the broad differential diagnosis of interstitial pneumopathies and a thorough and precise anamnesis.

- Early and precise diagnosis has significant effects on patients' quality of life and safety.

- The appropriate clinical approach includes the use oflatest-generation technology, especially in such a complicated group of diseases.

KEYWORDS

Pneumology, infectious diseases, internal medicine

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old male of Romanian origin and no relevant medical history was treated by emergency staff following an accidentat work. He had fallen into a wine storage container several meters deep and had lostconsciousness. On arrival at the emergency unit, he had severe respiratory failure and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) with a presumptivediagnosis of acute non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. Carboxyhaemoglobin levels were normal. After stabilization in the ICU, the patient was transferred to the internal medicineward with a diagnosis of carbon monoxide (CO) intoxication. He was febrile (up to 39ºC), alert and pale. Tachycardia was 110 beats per minute (bpm) and jugular distension was not present. The respiratory rate was 28 per minute, accompanied by severe breathing difficulty. Cracklingsounds could be heard from the middle and inferior lobes. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Partial oxygen pressure (PO2) was 53 mmHg, PCO2 was 41 mmHg, oxygen saturation was 88%, and levels of bicarbonate and lactic acid were normal. Chest x-ray showed an alveolar-interstitial pattern (Fig. 1).

Microbiology of sputum, including investigation for Koch's bacilli, yielded negative results. High-resolution thorax CT revealed well-defined centrilobular lung nodules 2–5 mm in diameter coveringthe lung parenchyma, particularly in the right hemithorax. Lesions were attributed to hypersensitivity pneumonitis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 - Well-defined centrilobular lung nodules affecting the entire pulmonary parenchyma, mainly in the right hemithorax

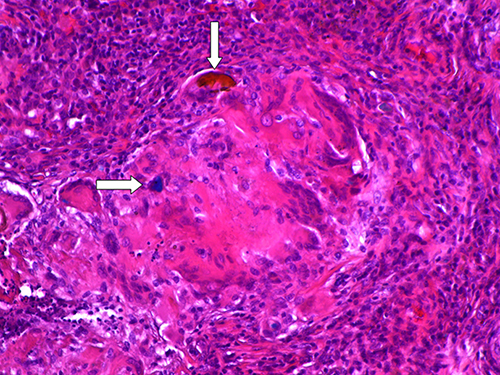

Immunological tests were positive for IgG precipitins and Aspergillus fumigatus, and negative for autoantibodies (anti-centromere, anti-SSA/Ro, anti-DNAds, anti-RNP, anti-histone, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic, anti-smooth muscleantibody). There was no history of previous exposure to Aspergillus. The CD4/CD8 ratio was 1.52. Empirical treatment for tuberculosis (TB) wasbegun, followed by intravenous steroids administered according to the guidelines of the Spanish Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery Society (Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica, SEPAR) for interstitial pneumopathies1. Treatment was well tolerated. Respiratory function tests revealed a severe restrictive pattern. Bronchoscopy was contra-indicated due tosevere respiratory failure. Consequently, an open lung biopsy was performed under anaesthesia. Pathological analysis of lung tissue showed a developmental-phaseforeign body giant cell granuloma, without central necrosis There were ubiquitous deposits of amorphous, slightly fibrillar foreign bodies, which we identified as grape traces (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 - Foreign body giant cell granulomas (top arrow) and amorphous matter, refractive, yellow and blue (bottom arrow)

Lung biopsy samples were cultivated, yielding a growth of A. fumigatus. PCR for mycobacterium complex was negative. Anti-TB treatment was discontinued and voriconazole was added to corticosteroids, according to Spanish guidelines[1,2]. The patient experienced a gradual clinical and radiological recovery, reaching NYHA functional class IIand a respiratory in the British Medical Research Council (MCR)[3]. After discharge, respiratory function tests remained stable. It was significant thatthe CO diffusing capacity (DLCO) was 67.6% and the Tiffenau index 69.37.

DISCUSSION

Accidental CO poisoning is an occupational hazard of the wine fermentation process,frequently leading to a fatal outcome. Within minutes, inhalation of CO levels above 6–10% in air causes shortness of breath, dizziness, sweating, nausea andloss of consciousness. Treatment involves the administration of highly concentrated oxygen[4]. Although broadly different in aetiology, diffuse ILD or interstitial pneumopathies are a group of diseases with similar clinical, radiological and functionalfeatures at presentation. The main differences allowing reliable classification are pathological changes involving the alveolar-interstitial structures. Suchchanges are associated with over 150 aetiological agents, although their epidemiology has not yet been clearly defined. From a clinical point of view,the most prominent symptom is dyspnoea during exertion or at rest, and cough. Other systemic signs such as fever, malaise, fatigue or arthromyalgia are also frequent. A wide range of diagnostic tests is required to rule outalternative diagnoses and correctly classify the subtype of ILD[1,5,6]. One of the causes of ILD is hypersensitivity pneumonitis, which is caused by theinhalation of organic matter. Diagnosis is based on several criteria, such as provocation tests, detection of specific serum antibodies, and clinicalimprovement after eliminating exposure to the allergen. Our patient failed to fulfil any of these criteria[1,5]. Most cases of pulmonary foreign body granulomatosis are associated with talc or cellulose used as excipients in medication or illicitdrugs. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reported cases of ILD secondary to the foreign body reaction caused by the inhalation of grape traces[7,8]. The clinical pattern of our patient was similar to other cases of ILD. The most prominent symptoms were cough, sputum production and dyspnoea. Thereare fewer reported cases of ILD in which acute respiratory failure, fibrosis or emphysema have been caused by foreign body inhalation. Diagnostic work-upusually includes bronchoscopy and lung biopsy7. Treatment in the acute phase is based on general life-support measures, while in the chronicphase, the effectiveness of corticoids has not been proven, and the results of immunomodulators are based on animal models[7,8]. We propose for this peculiar aetiology of ILD the name ‘Bacchus pneumonitis',since it was caused by the full immersion of the patient in a deep wine storage container.