ABSTRACT

The authors describe a case of a 48-year-old man who presented with fourweeks of fever, generalized malaise, weight loss, right upper quadrantabdominal pain and hepatosplenomegaly. He evolved with pancytopenia,bone marrow haemophagocytosis and hyperferritinaemia. Recent diagnosisof HIV infection, with the exclusion of other plausible causes, promptedthe diagnosis of haemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) secondary to HIV.Despite intensive care support and initiation of antiretroviral therapy,the patient died. HPS diagnosis secondary to HIV alone demands theexclusion of all the other secondary causes. The best approach includesearly diagnosis and specific treatment of the associated cause, wheneverpossible.

LEARNING POINTS

- HPS diagnosis is complex and in the context of HIV infection still constitutes a greatchallenge.

- Diagnosis of HPS secondary to HIV alone demands the exclusion of all the other knownsecondary causes of HPS.

- The best approach to treat HPS includes early diagnosis,adequate identification of prognostic factors, supportive care andspecific treatment of the associated cause, whenever possible.

- Consider HIV as a possible cause of HPS where no other cause has been identified.

KEYWORDS

Haemophagocytic syndrome, HIV

INTRODUCTION

Haemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) is a rare and potentially fatal disorder[1]. Its primary form is associated with underlying geneticabnormalities, usually presenting in childhood. Secondary HPS appearsmost frequently in the setting of infection, malignancy or autoimmunedisease [2, 3]. This type usually presents in adults and has a betterprognosis.

Probably underestimated, secondary forms are still being identified. Inthis setting, HIV has been associated with HPS with a wide range ofdisorders, namely viral, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal and protozoalinfections, malignancy, autoimmune diseases, related therapy and evenHIV itself [1]. The diagnostic guidelines proposed by the HistiocyteSociety have contributed to clarification of the diagnosis [4].Naturally, the diagnosis of HPS secondary to HIV infection is onlypossible in the absence of other plausible causes. The authors report aHPS secondary to HIV and discuss some particular aspects.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old heterosexual man was admitted to the hospital after fourweeks of fever, generalized malaise, weight loss and a right-upperquadrant abdominal pain. Besides smoking and a considerable alcoholintake (80–110 g/day), he had no significant travel, drug or medicalhistory. On admission, the patient appeared acutely ill, with mildconfusion, fever and hypotension, without other abnormal physicalfindings. Laboratory tests (Table 1) showed 87,000/mm3platelets (150,000–400,000/mm3), normochromic and normocytic anaemia(Hb=7.4 g/dl), lymphopenia (860/μl) (1500–4000/mm3), elevated C-reactiveprotein (157 mg/l) (<1.0 mg/l), low albumin (2.5 g/dl) (3.0–5.0g/dl), international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.3 and elevated serumferritin levels (7867 ng/ml) (12.8–454 ng/ml).

| Variable | Reference range | Day 1 | Day 9 (Day 1 HAART) |

Day 19 (Day 10 HAART) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin /mg/dl) | 13-17 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 4.2 |

| Leucocytes (/mm³) | 4,000-11,000 | 2,900 | 2,620 | 2,520 |

| Neutrophils (/mm³) | 2,000-7,500 | 2010 | 2120 | 1,590 |

| Lymphocytes (/mm³) | 1,500-4,000 | 860 | 210 | 630 |

| Platelets (/mm³) | 150,000-400,000 | 87,000 | <10,000 | <10,000 |

| INR | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 220-450 | 402 | 307 | - |

| Ferritin (ng/dl) | 12.8-454 | 7,867 | 3,049 | 2.109 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 40-160 | 151 | 52 | - |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3-5 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.2-1.00 | 0.3 | 9.9 | 4.1 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/I) | 10-34 | 27 | 32 | 32 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/I) | 10-44 | 8 | 7 | 16 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/I) | 45-122 | 58 | 37 | 79 |

| y-Glutamyl transpeptidase (U/I) | 10-66 | 17 | 12 | 51 |

| Sodium (mmol/I) | 135-145 | 144 | 153 | 167 |

Table 1 - Laboratory data

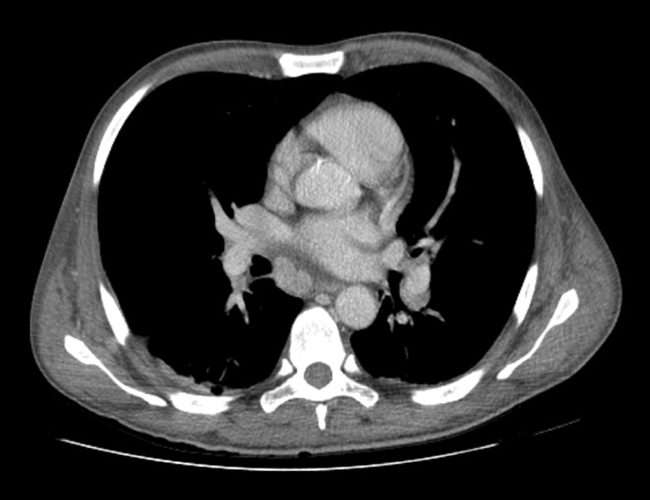

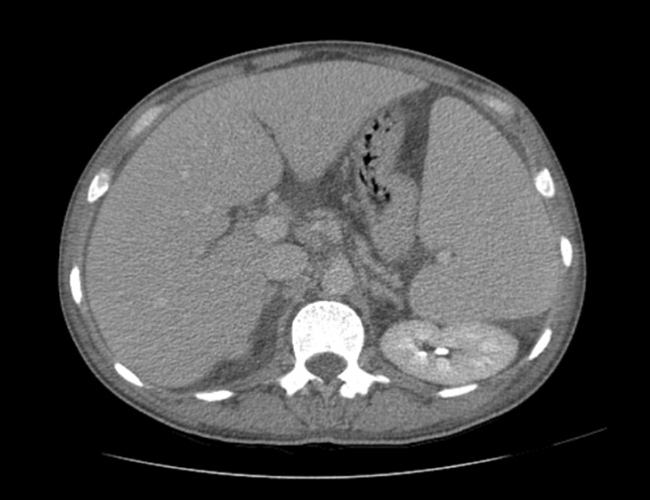

Chest radiography showed small bilateral pleural effusions, confirmed by ultrasound, which also revealed homogeneous mild hepatosplenomegaly andmoderate ascites. Thoracoabdominal CT also showed diffuse lympadenopathy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1a,b - Thoracoabdominal CT with diffuse lympadenopathy (<2 cm) and homogeneous mild hepatosplenomegaly.

Peritoneal fluid was tested and showed an exudate with an elevatedmononuclear count, low adenosine deaminase and negative PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. HIV testing was positive with HIV RNA of 101,000 copies/ml, and a TCD4 cell count of 38/mm3 (2.4%).

Serology for syphilis, Brucella, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, Toxoplasma gondii and hepatitis A, B and C was negative.

At this point, considering the recent HIV diagnosis, with severeimmunosuppression and a presentation of a systemic illness (haematologicfindings, pleural and peritoneal effusions and signs of activation ofthe reticuloendothelial system), haematological malignancy, tuberculosisand hepatic disease were hypothesized as the most probable differentialdiagnosis. Nevertheless, a sepsis also had to be considered and thepatient was admitted to the intermediate care unit and started onbroad-spectrum antibiotic therapy.

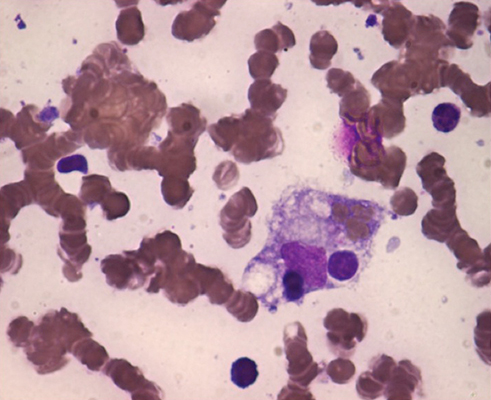

A bone marrow sample was obtained and showed features of hypocellularity and haemophagocytosis (Fig. 2) but no evidence of malignancy.

Fig. 2 - Bone marrow with macrophage phagocytosis of erythroblasts (×100 Giemsa stain).

The analysis of blood, bone marrow and lymph node tissue showed no signof lymphoproliferative disorder and was negative for bacteria,mycobacterium and fungi.

On the fourth day of inpatient care, despite broad-spectrum antibiotics,the clinical state of the patient deteriorated with multiple organfailure and he was admitted to the intensive care unit, requiringvasopressor support and invasive mechanical ventilation.

A diagnosis of haemophagocytic syndrome, most probably related to HIVinfection, was assumed, since no evidence of other infection orhaematologic disease was found. The patient was started on HAART(tenofovir, emtricitabin, lopinavir/ritonavir), prednisolone (1 mg/kgdaily) and immunoglobulin (1 g/kg for two consecutive days).

Haematologic dysfunction evolved with deteriorating pancytopenia, liverdysfunction with progressive hypoalbuminaemia and hyperbilirubinaemiaand prolongation of INR. He also developed a state of increased vascularpermeability, unresponsive to albumin administration, and associatedrefractory shock.

Despite all the above treatments, the patient's clinical state continued to deteriorate and death occurred at day 10 of HAART.

DISCUSSION

The pathophysiology of HPS is best understood for the primary form ofHPS, in which genetic defects in proteins that play an important role incytolytic secretory pathway [7] lead to excessive activation of T cellsand subsequently to increased cytokine secretion and hyperactivation ofmacrophages [1]. The pathogenesis of secondary HPS is less clear and inthe setting of HIV infection it is probably related to acquired defectsin cellular cytotoxicity [1].

Clinical features of HPS are consistent with this state of immunehyperactivation, including fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegalyand jaundice, as well as cytopenia and impaired liver function. Thesenonspecific features have a wide differential diagnosis in the contextof HIV. Indeed HPS may be mistaken for many other disorders, mostfrequently lymphoproliferative diseases or infections. In this case theacute clinical presentation suggested a septic status although with aninconsistent evolution (no response to broad-spectrum antibiotictherapy, vasopressor support and albumin infusion). Efforts to excludeinfections and lymphoproliferative disorders were made. The clinicalfindings of fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias, bone marrowhaemophagocytosis and hyperferritinaemia, fulfilled five of theabove-mentioned criteria, suggesting HPS as the most probable diagnosis.No trigger but HIV was found. The main aetiology for HPS in HIVpatients is infection. In the largest study to date, only 5% of patientswere found to have no underlying cause of HPS other than HIV itself[5].

The proposed management for the primary form of HPS, the HLH-94protocol [4], has proven efficacy in Epstein–Barr virus-associated HPSbut not in HIV infection. For HPS associated with HIV infection,treatment should be individualized, with supportive care promptlyinitiated and treatment of potential triggers. The potential efficacy ofHAART has been described [1], although the risk of immunereconstitution syndrome should be considered. Also, high-dosecorticosteroids are commonly used as well as intravenous immunoglobulin(IVIg) [1]. In this case, supportive care, empiric broad-spectrumantibiotics, corticosteroid therapy, IVIg and HAART were instituted,none with any obvious beneficial effect.

The prognosis of HPS was significantly improved after HLH-94introduction for primary forms [15]. A mortality rate of 31% at 3 monthsfor HPS associated with HIV has been described [5]. Prognostic factorsin the setting of HPS associated with HIV are still to be identified,although ICU admission, cytopenias andhaemotological/malignancy-associated disorders are expected to berelevant. Specifically related to HIV, low CD4 cell count is expected tobe a possible prognostic indicator.

CONCLUSIONS

HPS diagnosis is complex and in the context of HIV infection stillconstitutes a great challenge. The best approach seems to includeadequate identification of prognostic factors, early diagnosis andspecific treatment of the associated cause, whenever possible.